In August 2024, more than 10,000 residents in Jianchang County faced a deluge that submerged homes, washed away farmlands, and claimed lives—tragically underscoring how vulnerable rural China remains to the twin threats of extreme weather and governance failures.

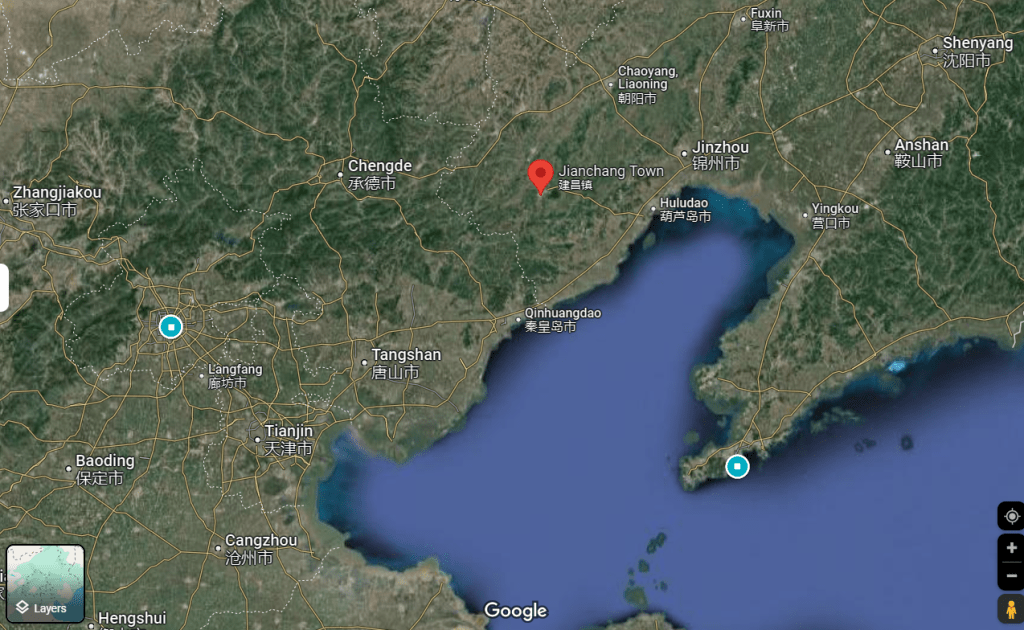

A case study of the devastating August floods in Jianchang County, Liaoning Province, provides a revealing lens into broader issues that plague rural areas, along with the governance structures tasked with protecting them. While there have been other more high-profile flood events across the country in 2024, the Jianchang County flood interested me because of my prior in-country experience in northeast China.

By examining this event through a structured 5 Why’s analysis, we can unpack the root causes and systemic failings that transformed a natural disaster into a humanitarian crisis.

Context: Widespread flood events across China

The scale and persistence of floods across China this year have been monumental, exposing not only the country’s vulnerability to climate change but also systemic weaknesses in disaster management.

According to Reuters, China experienced significant economic and humanitarian impacts from natural disasters in the third quarter of 2024, with direct losses reaching 230 billion yuan ($32.3 billion), more than double the 93.16 billion yuan recorded in the first half of the year.

China’s Ministry of Emergency Management stated that over 84 million people were affected in the first nine months of 2024, 836 people were reported dead or missing, and nearly 3.35 million required urgent resettlement, alongside extensive damage to homes and crops.

As reported by Carbon Brief, Climate patterns such as El Niño, combined with monsoon dynamics and human-driven greenhouse gas emissions, have led to more frequent and severe rainstorms and floods in China, with 2024 far exceeding historical averages. Additionally, urban factors such as poor city planning, land subsidence, and infrastructure design further amplify flood risks, highlighting the compounded impact of both climatic and human influences on extreme weather events.

1. Why did Jianchang County suffer severe flood damage?

In late August 2024, heavy rainfall and the sudden release of water from upstream reservoirs inundated a section of the Daling River basin in the Huludao region of Jianchang County. The flood submerged homes and farmland, washed away vehicles, and cut off communities from essential communications. Eleven people were reported dead and 14 missing due to the flooding, while over 7,000 residents were evacuated to Huludao City.

As reported by human rights platform Red Censor:

According to the Liaoning Provincial Meteorological Department, from August 18 to 20, some areas in Huludao experienced torrential rain. Jianchang County’s Heshanke Township, Leijiadian Township, Heshangfangzi Township, Yangmadianzi Township, and Datun Town were severely affected, resulting in communication disruptions in four villages.

On the 19th, Jianchang County Flood Control and Drought Relief Headquarters announced that the water level in the Palace Mountain Reservoir had reached the flood limit, prompting the opening of floodgates at 3 p.m. with a discharge rate of 50 cubic meters per second for a planned seven-day release.

This combination of natural and man-made factors overwhelmed the county’s limited infrastructure, particularly in the small, low-income towns along the Daling River that were worst effected, leaving residents to fend for themselves in the critical days following the disaster.

The immediate trigger was the uncoordinated release of reservoir water, which amplified the impact of the rainfall. This decision, while likely necessary to prevent dam failures, caught downstream communities unprepared, turning a manageable crisis into a catastrophic one.

2. Why was the water release so damaging?

The reservoir water release was executed without adequate warning or communication to downstream residents. Without sufficient time to prepare, communities along the Daling River were blindsided, resulting in severe damage and loss of life. While pre-emptive releases are common in dam flood management in China, the lack of an early warning system revealed a critical gap in disaster preparedness.

The decision to release the water may have been a necessary precaution to prevent dam failures, but the lack of communication caught downstream communities completely off guard, exacerbating the disaster. This incident raises critical questions about the decrepit state of much of China’s hydrological infrastructure, which has long been subject to scrutiny for engineering flaws and underinvestment.

Many of the country’s dams and reservoirs are aging, and their maintenance has not kept pace with China’s rapid development and the growing frequency of extreme weather events. The lack of investment in infrastructure, such as modernising dams and reservoirs, further exacerbates the problem.

This failure reflects a broader issue in China’s hydrological management systems, particularly in more isolated rural areas, which lack integration and coordination between local, regional, and national levels. Generally, local governments are responsible for managing reconstruction efforts after natural disasters, while the central government oversees planning and financing. Disparate systems and poorly maintained communication channels exacerbate the risks posed by extreme weather events.

3. Why was there no proper warning or coordination?

Earlier in the summer, Politburo Standing Committee member Li Qiang stated that “We must strengthen disaster forecasting, warning and emergency response, and fully implement the “call-and-response” mechanism of disaster warning that reaches the grassroots level.” The fragmented disaster management framework hampers the ability to respond swiftly and effectively, especially in rural areas where resources and expertise are often lacking.

The apparent absence of effective communication stems from systemic weaknesses in disaster management. Local officials, tasked with making crucial decisions like reservoir releases, operate within a fragmented governance framework. Coordination between local water resources bureaus and national disaster management bodies is often inadequate, leading to inconsistent implementation of protocols and communication failures.

China has made significant strides in flood and drought preparedness through initiatives like the sponge cities program (SCP) and large-scale investments in water conservancy projects, aimed at ameliorating flood risk in larger population centres. However, challenges remain, including the SCP’s limitations in handling extreme rainfall events, fragmented regional planning, and social vulnerabilities that exacerbate flood impacts, along with a need for a more integrated, equitable, and adaptive approach to disaster management in rural areas outside of the larger cities.

4. Why are there gaps in disaster management systems?

The centralisation of governance in China’s political system creates a significant disconnect between national-level decision-making and local implementation. While policies may be designed Beijing, their execution often falls to poorly resourced local officials who lack the tools and autonomy to act decisively. This centralisation also discourages proactive measures like infrastructure investments or community preparedness, as local leaders are evaluated more on their ability to avoid scandals than on their long-term planning.

In China’s political system, decisions such as the release of water from a dam are typically handled by local and regional authorities. In relation to dams and flood management, every county has a County Water Resources Bureau that is responsible for managing local infrastructure, including reservoirs and dams. In an emergency, the decision to release water would likely involve the director of this bureau, along with technical engineers and emergency management personnel.

Ultimately, local Party Secretaries bear responsibility for overseeing the proper functioning of water infrastructure. Failures to manage these systems effectively has rightly resulted in public blame and anger being placed on local leaders, with a flow-on impact on public confidence in the Chinese Communist Party as a whole, undermining its legitimacy at a time when economic contraction is already hitting people hard.

This dynamic leaves rural communities, such as those in Jianchang County, particularly vulnerable. They face a dual burden of aging infrastructure and insufficient disaster response mechanisms, both of which stem from systemic underinvestment and a lack of accountability in governance structures.

5. Why is the system so centralised and fragmented?

At the root of these issues lies China’s political structure, which emphasises top-down control and prioritises maintaining social stability. Local officials operate under immense pressure to avoid high-profile failures that could attract scrutiny from the central government. In this high-stakes environment, short-term decisions, like releasing reservoir water without proper communication, often take precedence over long-term strategies for resilience.

The decision to release water from the dam in Jianchang County was shaped by a complex mix of incentives and risks inherent in China’s political system. Local officials are judged based on their ability to maintain social stability, prevent disasters, and avoid scandals, with career advancement closely tied to performance evaluations.

However, within the institutional logic in which local officials operate, as described by Rowan Callick in his book Party Time, this incentive structure drives officials to prioritise the short-term success of preventing dam failure, without considering the follow-on consequences of that choice. It follows that pre-emptively releasing water to avoid the potential failure of aging dams could have been seen as a positive action demonstrating competent crisis management in avoiding a larger disaster.

In his book The Party, Richard McGregor argues that decisions, even down to local levels, are shaped by the need to protect the Party’s image and avert any actions that could lead to public dissent or social unrest. The fear of being scapegoated for a disaster can lead officials to adopt a defensive, risk-averse stance, where swift action is prioritised to demonstrate loyalty to the Party and competence in crisis management.

A dam collapse causing significant loss of life and major property damage, exposing local officials to severe punishments, ranging from demotion and public reprimands to removal from office (or worse). Party discipline in Xi Jingping’s China is extremely strict, and failures in disaster management are grounds investigations from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), particularly if negligence or corruption is suspected. One can therefore understand the pressure local hydrological managers would feel to do whatever is necessary to keep dams intact.

The actual consequences of the decision to release dam water on the Daling River were severe. Indeed, from an outside perspective, it seems obviously foolish that local officials would release so much water from upstream dams, all but replicating the consequences of a dam failure.

Root cause: Rigid governance ill-suited to dynamic disaster resilience

The Jianchang County floods are a reminder that effective governance is as critical as physical infrastructure in safeguarding communities from flood events.

Even in China’s controlled media environment, the Jianchang flood and others have sparked public outrage. This does not bode well for county-level bureaucrats who are likely to be held responsible by the central government. In this high-stakes environment, local officials are caught in a knot between their desire for self-preservation, significant risks associated with poor infrastructure, the need for decisive disaster management to protect communities, and the risks of perceived failure in a political environment of extreme Party discipline.

China’s centralised political system, designed to maintain control and stability, inadvertently undermines its ability to manage complex, multi-layered crises like flooding. The system’s rigidity hampers proactive disaster management and fosters a culture of reactive decision-making that often worsens the impact of natural disasters.

The Jianchang County tragedy, along with the many other flood disaster that occurred across China through 2024, underscore the urgent need for systemic reforms in China’s disaster management systems. Without systemic reforms to decentralise disaster management and improve transparency, such crises are highly likely to recur.

The floods in Jianchang County were not merely a natural disaster but a symptom of deeper governance issues in China. As climate change continues to challenge the nation’s disaster resilience, these systemic weaknesses represent a growing risk for the Chinese Communist Party.

[…] Climate patterns such as El Niño, combined with monsoon dynamics and human-driven greenhouse gas emissions, have led to more frequent and severe rainstorms and floods in China, with 2024 far exceeding historical averages (Tan & Song 2024). Additionally, urban factors such as poor city planning, land subsidence, and infrastructure design further amplify flood risks, highlighting the compounded impact of both climatic and human influences on extreme weather events (Habib 2024). […]