- Millenarian movements

- Case studies

- Rise of millenarian movements during systemic crises

- Learning activity: Comparing historic and contemporary millenarian movements

- Reference

The idea for this article emerged while I was preparing a guest lecture for an Asian Studies class on the making of modern Asia and the role of modernity in Korea.

Modernity, at its core, embodies a rejection of the past and an embrace of Enlightenment rationalism, envisioning a future shaped by scientific and technological progress. It is a worldview rooted in individualism, reductionism, and separation, with social hierarchies that diverged radically from those of the dynastic, feudal-agrarian bureaucratic systems that characterised societies like Joseon Korea. This sweeping shift formed the backdrop for the Donghak Rebellion (1894-1895), a precursor to the collapse of the Yi Dynasty and Joseon Korea’s annexation by Imperial Japan.

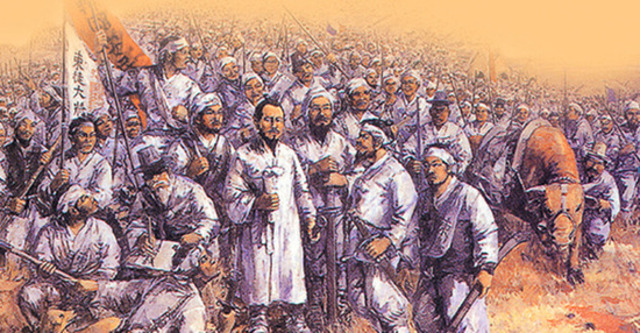

As I delved deeper, it struck me that elements of the Donghak Rebellion resonated with other 19th-century uprisings across East Asia, including the Taiping Rebellion in China (1850-1864), the Satsuma Rebellion in Japan (1877), and the Boxer Rebellion in China (1899-1901). These movements arose amidst the systemic breakdown of the Sino-centric international order and the transformative pressures of modernisation.

In these contexts, modernity often equalled rupture—disrupting entrenched social, political, and economic systems—and this rupture became fertile ground for millenarian movements.

In this article, I compare these East Asian case studies to identify key features that characterise millenarian movements during periods of systemic crisis. I also outline a discussion-based learning activity for undergraduate students in International Relations, Asian Studies, and Comparative Politics, inviting them to examine these historical movements and draw parallels with contemporary examples.

Through this exploration, we can better understand how such movements emerge as profound responses to moments of upheaval and transformation.

Millenarian movements

A millenarian movement is a social or religious movement rooted in the belief in an imminent, transformative change that will bring about a utopian era or a radical reordering of society. Often arising in times of crisis, these movements are typically driven by dissatisfaction with existing socio-political structures, a sense of moral or spiritual decay, and the promise of salvation or renewal.

Millenarian movements frequently feature charismatic leaders, apocalyptic visions, and collective action aimed at overthrowing perceived oppressors or unjust systems to usher in an idealised future.

In researching for that guest lecture, it also occurred to me that the millenarian movements I’d identified in 19th century East Asia shared attributes with some movements that have arisen in our current time in the West.

As a new industrial revolution driven by artificial intelligence (AI) and decarbonisation unfolds, it is already eliciting significant resistance and cultural disruption. Like earlier waves of transformative change, this resistance will stem from deep-seated anxieties about economic displacement, the erosion of traditional identities, and the unequal distribution of progress. These fears, when combined with the rapid pace of innovation, could lead to widespread manifestations of backlash.

Case studies

First, let’s briefly examine our four case studies from 19th century East Asia.

Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864)

The Taiping Rebellion, led by charismatic leader Hong Xiuquan, was a profound violent upheaval in 19th-century China that irrevocably altered the Qing dynasty and claimed the lives of over 20 million people.

The First Opium War and subsequent unequal treaties with Western powers had shattered Qing China’s economic and political stability, creating a disequilibrium as traditional Confucian structures struggled to address new challenges arising from modernisation and foreign influence.

Inspired by Christian teachings and believing himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ, Hong founded the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom in 1851. His movement, rooted in the ideals of shared property and anti-Manchu sentiment, garnered immense support among impoverished peasants in southern China. The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom established Nanjing as its capital following a whirlwind military campaign.

However, the rebellion’s early victories were undermined by internal discord and leadership struggles, compounded by strategic errors, which severely fractured the movement. Attempts to expand into key cities such as Beijing and Shanghai failed due to resistance from Western-back Qing forces. By 1864, the Qing army besieged and recaptured Nanjing, marking the effective end of the rebellion after Hong’s suicide. While remnants of the Taiping forces persisted until 1868, their influence had largely waned.

The Taiping movement introduced radical reforms, including gender equality, communal land ownership, and the abolition of foot-binding and opium use, which set it apart from traditional Qing rule. Their society, driven by strict discipline and a vision of divine retribution, inspired both fervent loyalty and fear. Although defeated, the Taiping Rebellion left an enduring legacy, irrevocably weakening the Qing dynasty and influencing future Chinese revolutionary movements.

Satsuma Rebellion (1877)

The Satsuma Rebellion was a samurai-led revolt against Japan’s fledgling Meiji government, lasting from January to September 1877. Originating from Satsuma, a domain pivotal in the Meiji Restoration, the uprising was driven by dissatisfaction among former samurai whose societal status was abolished by the Restoration’s military and cultural reforms. The ultimately unsuccessful rebellion marked the definitive end of the samurai class, replacing them with conscript armies and modern warfare.

The rebellion was led by Saigō Takamori, a reformist who became disillusioned with the Meiji government’s perceived corruption and rapid Westernisation, which many samurai viewed as a betrayal of their traditional values. He championed the samurai cause and advocated for war with Korea to restore their purpose and honour. Saigō resigned after the rejection of his war plans, in the process gaining widespread support among disaffected ex-samurai. This dissatisfaction escalated into rebellion as Satsuma became increasingly autonomous, with Saigō and his followers forming a stronghold against the central government. By 1876, Saigō’s defiance of imperial authority set the stage for open conflict.

The Satsuma Rebellion can be seen as a millenarian movement because it embodied a yearning for a return to a perceived golden age of samurai values and governance, rejecting the sweeping modernisation and Westernisation of the Meiji era.

Saigō Takamori and his followers framed their struggle as a moral and spiritual crusade against corruption and the abandonment of traditional Japanese ideals. The rebellion’s rhetoric and symbols, such as banners proclaiming “new government, rich virtue”, reflected a vision of societal renewal rooted in samurai ethics and resistance to foreign influence.

Although it ultimately failed, the movement reflected deep discontent with the pace of change and the desire for a utopian restoration of Japan’s feudal past. The successful suppression of the rebellion reinforced the legitimacy of the new regime and allowed Japan to emerge as a unified and modern nation-state capable of resisting colonial encroachment, unlike neighbouring East Asian powers.

Donghak Rebellion (1894-1895)

The Donghak Rebellion of 1894 was a pivotal uprising in Korea, rooted in widespread dissatisfaction with the socio-economic inequalities, government corruption, and foreign interference that characterised the late Joseon period. Donghak, a syncretic religion blending traditional Korean beliefs with Christian influences, provided a unifying ideology for the discontented peasantry, advocating for equality and resistance to foreign domination.

Founded by Choe Je-u and later led by under the charismatic leadership of Jeon Bong-jun, the movement escalated into a full-scale revolt, successfully defeating government forces in southern Korea before foreign powers intervened. The rebellion’s suppression highlighted Korea’s vulnerability to both internal instability and the imperial ambitions of China and Japan, with their subsequent clashes leading to the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895).

The rebellion drew strength from the Donghak religion’s spiritual framework, which combined monotheistic elements, shamanistic rituals, and unique beliefs promoting human equality and a vision of societal renewal. The Donghak rejected the established order, challenging the Joseon government’s neglect of the peasantry and its failure to address rampant inequality and over-taxation.

The religion’s revolutionary ideals, such as the belief in a new world cycle and the notion that all humans embodied divine essence, made it a direct threat to the Joseon dynasty’s legitimacy. The rebellion’s mix of spiritual fervour and social reform ideals resonated with the masses but also attracted harsh suppression from both the Korean authorities and foreign military forces.

The Donghak Rebellion exemplified a millenarian movement through its vision of societal renewal and the promise of a transformative new era that would replace the existing corrupt and oppressive order. Rooted in the teachings of Donghak, the movement embraced beliefs in human equality and the cyclical renewal of the world, with its founder Choe Je-u envisioning an end to the current “5,000-year cycle” (Jeoncheon) to make way for a new, harmonious world (Hucheon). These ideas inspired the peasantry to rise against the socio-economic injustices of the Joseon state and to reject foreign domination, positioning their struggle as not merely political but deeply spiritual and apocalyptic in nature.

Although ultimately crushed, the Donghak Rebellion exposed the systemic weaknesses of the Joseon state and its inability to maintain sovereignty amidst the competing influences of China and Japan. The uprising’s failure did little to resolve the underlying issues that plagued Korean society and, instead, underscored Korea’s vulnerability to foreign domination, culminating in Japanese annexation in 1910.

Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901)

The Boxer Rebellion was a desperate, chaotic reaction to the forces of colonialism, modernisation, and the breakdown of the traditional Sino-centric international order. The “Boxers,” practising martial arts and invoking millenarian beliefs, sought to expel foreign powers and their perceived cultural and spiritual pollution. The Qing dynasty’s failure to protect China from foreign domination created a disequilibrium that left many Chinese feeling powerless and betrayed.

The Boxers’ movement filled an emotional void for peasants and other disenfranchised groups, offering a sense of agency and purpose through its anti-foreign, anti-Christian rhetoric. While the movement lacked a singular charismatic leader, its collective fervour brought temporary unity to disparate groups. However, the chaos they unleashed, including the siege of foreign legations in Beijing, ultimately invited a devastating military intervention from the Eight-Nation Alliance of Western powers.

The Boxer Rebellion hastened the ultimate breakdown of the Qing dynasty by exposing its inability to confront both internal and external threats effectively. While the rebellion was initially encouraged by elements of the Qing court, its escalation into a full-blown conflict with the Eight-Nation Alliance revealed the dynasty’s incompetence in managing foreign relations and internal dissent. The defeat of the Boxers deepened China’s humiliation and drained its resources, further delegitimising the Qing regime and leading inexorably to its collapse in 1911.

The Boxer Rebellion exhibited millenarian qualities through its apocalyptic vision of purging foreign influence and restoring harmony to a China plagued by socio-economic strife and imperial exploitation. Rooted in the belief that their martial rituals rendered them invulnerable, the Boxers perceived themselves as divinely empowered to enact a transformative cleansing of both foreign powers and their domestic collaborators, including Chinese Christians.

Their actions were motivated by a desire to return to a golden age free from foreign domination and moral corruption, echoing the millenarian theme of societal renewal through revolutionary upheaval. This spiritual fervour, combined with their utopian vision of a purified and independent China, positioned the rebellion as a quintessential millenarian movement.

Comparative observations

Each of these movements reflected profound dislocations caused by modernisation, the erosion of the Sino-centric world order, and the pressures of colonialism. They arose in moments of disequilibrium, offering charismatic leadership or unifying ideologies to fill the emotional voids created by social and political decay.

While they were ultimately defeated, these movements played crucial roles in the broader process of East Asia’s transformation, bringing temporary order amidst chaos and paving the way for the 20th century’s revolutionary changes.

While each movement arose from unique circumstances, they collectively highlighted systemic weaknesses in their respective regimes. The Taiping Rebellion and Boxer Rebellion both revealed the Qing dynasty’s fragility, directly contributing to its downfall. The Donghak Rebellion exposed the structural vulnerabilities of the Joseon dynasty, leading to its eventual subjugation by Imperial Japan.

In contrast, the Satsuma Rebellion, though a significant challenge to the Meiji government, ultimately strengthened Japan’s ruling regime, demonstrating its ability to adapt and consolidate power amidst the tumult of modernisation. These movements illuminate the varying capacities of East Asian states to navigate the transformative pressures of the 19th century.

Rise of millenarian movements during systemic crises

Periods of upheaval and systemic breakdown are fertile ground for the emergence of millenarian movements, particularly those underpinned by quasi-religious or conspiratorial beliefs. Such crises breed widespread social discontent, anxiety, and a deep erosion of trust in established institutions. In these moments, individuals seek explanations for their suffering, alternatives to the failing status quo, and leaders or ideologies that promise to restore order and justice. A variety of interconnected factors help to explain why these movements thrive in such contexts.

“If history reveals sets of events or actions that foretold what was about to occur in the past, they could prove to be valuable lead indicators for anticipating whether a similar event is likely to unfold in the future.” (Pherson and Heuer 2020, p. 370)

Disequilibrium and breakdown

These movements are a response to disequilibrium and breakdown. Resistance to modernisation and cultural disruption frequently underpins these movements. Crises linked to rapid modernisation or external influences often provoke backlash from communities that feel alienated or marginalised by change. These movements commonly frame their goals as defending traditional values against external threats.

A key driver is the crisis of legitimacy that frequently accompanies systemic breakdowns. During such times, governments and institutions lose their credibility, often due to economic hardships, political corruption, or military failures. This creates a vacuum of authority that populist movements eagerly fill. They frame their leaders as divinely sanctioned or morally superior figures, uniquely capable of addressing grievances.

Economic disparity and social inequality further fuel such movements. Economic crises exacerbate existing disparities, leaving large portions of the population struggling with poverty, unemployment, and a loss of status. This environment fosters resentment towards perceived elites, who are often blamed for the crisis. Populist rhetoric typically positions such movements as champions of the oppressed, mobilising support from those who feel left behind.

Filling social and emotional voids

These movements thrive during systemic breakdowns because they fulfil deep psychological, social, and political needs. They provide explanations for suffering, foster collective identities, and inspire hope in times of despair.

Periods of instability intensify the psychological need for certainty. In the face of uncertain futures, quasi-religious and conspiratorial movements provide simple, compelling narratives that offer moral clarity and purpose. These narratives often identify scapegoats—elites, foreigners, or marginalised groups—blaming them for societal suffering and promising redemption.

Adding to this dynamic is the emotional appeal of apocalyptic or millenarian ideals. These ideologies thrive during times of crisis, offering visions of imminent transformation that will replace the broken order with a utopian future. Such promises galvanise followers, instilling a sense of urgency and hope even in the direst circumstances.

Crises also erode social cohesion, fragmenting societies along class, ethnic, or ideological lines. Movements offering unifying identities or collective purposes resonate strongly in such environments. The amplifying effect of grassroots mobilisation is another critical factor. Crises disproportionately impact rural and marginalised communities, creating fertile conditions for movements that validate their struggles and offer hope.

The role of a charismatic figure

A recurring element in these movements is the role of charismatic leadership. During crises, leaders emerge as symbols of hope and change, rallying support through personal magnetism and their ability to articulate the frustrations of the masses. These figures often frame their missions in religious or conspiratorial terms, presenting their struggles as part of a larger moral or cosmic battle. Hong Xiuquan, leader of the Taiping Rebellion, exemplified this, combining charisma with religious visions to attract millions to his cause.

Conspiratorial thinking plays an equally significant role in the rise of such movements. Crises often prompt people to seek simple explanations for their suffering, and charismatic figures preaching conspiracy theories provide this by attributing hardship to deliberate actions by malevolent actors. Conspiratorial and quasi-religious frameworks in particular provide moral and spiritual cohesion, creating solidarity among disparate groups. In Korea, the Donghak Peasant Revolution united rural communities with its spiritual teachings and opposition to corruption and foreign intervention.

Learning activity: Comparing historic and contemporary millenarian movements

This activity is designed for students studying International Relations, Comparative Politics, and Asian Studies. Based on the structured analytical technique known as Structured Analogy, it introduces students to millenarian movements in 19th-century East Asia and connects historical dynamics to the emergence of comparable movements in the 21st century. The activity emphasises collaborative learning, critical thinking, and the application of historical frameworks to modern contexts.

Objective

In this activity, students will complete the following:

- Analyse key characteristics of the four 19th-century millenarian movement case studies from East Asia.

- Identify similarities and differences between these movements and contemporary movements in the 21st century.

- Explore how systemic breakdowns foster millenarian ideologies.

Preparation

This class activity will be most stimulating and entertaining for students if they prepare before the class.

Student preparation (before class): Student should prepare for this activity by reading peer-reviewed sources set as texts for this class by the instructor. They should also bring a personal device (laptop, tablet, or phone) for internet-based research that may help them during the activity.

Instructor preparation (before class): The instructor should prepare reading materials, discussion prompts for small-group activities and gather resources on both historical and modern movements for students to access during the activity.

Activity Structure

Introduction

Lecture overview (10 Minutes): The instructor provides a brief overview of millenarian movements in East Asia—focusing on the Taiping Rebellion, Satsuma Rebellion, Donghak Rebellion, and Boxer Rebellion—highlighting themes such as charismatic leadership, resistance to modernisation, and social discontent.

Individual brainstorm (10 Minutes): Pose guiding questions to engage the class, which students will respond to individually by making notes, so they will have discussion points prepared for their groups discussions.

Guiding questions may include the following…

- What are the common features of millenarian movements?

- How do systemic breakdowns foster such movements?

- What are the pro’s and con’s of comparing millenarian movements across different cultures and time periods, or analogising historic millenarian movements with current-day movements?

Students should avoid overly polemical and loose historical analogies by rigorously examining both the similarities and differences between phenomena, ensuring their reasoning is grounded in a careful analysis of root causes to avoid flawed conclusions (Pherson and Heuer 2020, p 374).

Small-Group Analysis

Part A: Historical case analysis (20 Minutes)

In groups of 3–4, students analyse the Taiping, Satsuma, Donghak and Boxer Rebellions—drawing on lecture material, assigned readings, and in-class online research—based on the guiding discussion questions.

Questions for discussion:

- What social, political, and economic factors contributed to these movements?

- How did these movements use spiritual or cultural traditions to mobilise support?

- What role did charismatic leadership play in driving these movements?

Part B: Connecting to modern movements (20 Minutes)

Student groups identify parallels between 19th-century millenarian movements and 21st-century movements. Use personal devices to research modern cases (e.g., populist movements, conspiracy-driven ideologies, or grassroots uprisings).

Questions for discussion:

- What similarities exist between historical and modern movements in terms of leadership, mobilisation, and narratives?

- How do modern movements use technology to amplify their reach compared to historical movements?

- What are the implications of systemic breakdown in fostering these movements today?

Group Presentations

Presentations (30 minutes): Each group presents their findings to the class in a 5-minute presentation.

Students should discuss these key elements from their case analyses:

- Key factors driving historical millenarian movements.

- Parallels and divergences with modern movements.

- Insights into how systemic breakdown fosters populist or millenarian ideologies.

Concluding discussion

Class debrief (30 minutes): The instructor facilitates a discussion tying together group findings.

- In what ways are/aren’t the forces of political and economic change present today equivalent to those rupturing 19th century East Asia?

- How do the lessons from 19th-century East Asia help us understand today’s political movements?

- In what ways are today’s movements different from the 19th century East Asian case studies?

- What strategies can policymakers today use to address systemic crises without fostering divisive or destructive ideologies?

Learning Outcomes

This activity combines historical inquiry with contemporary relevance, helping students draw connections between past and present. By engaging with these complex dynamics, students gain deeper insights into the mechanisms of societal transformation and the enduring patterns of human behaviour during periods of crisis. Specifically, students will…

- Develop a nuanced understanding of how breakdowns of political-economic systems, in the context of modernity, industrialisation and colonialism have led to millenarian movements in East Asia.

- Strengthen case study, strategic thinking and comparative analytical skills by comparing historical and modern movements, both in East Asia and beyond.

- Foster collaborative learning and the ability to articulate complex ideas.

Recognising the dynamics underpinning these movements is helpful in the present day to help us address the root causes of our current poly-crisis, mitigate as much as possible the potential for divisive or destructive outcomes, and adapt to emergent systemic change.

Reference

Randolph H. Pherson and Richards J. Heuer Jr. (2021) Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis. 3rd Ed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.