- Elements of information warfare

- Information warfare vs public relations and advertising

- Detecting deception in the fog of information warfare

- Learning activity

- Reference

In the current political environment of widespread disinformation, epistemological rigour and information hygiene are super-important skills to cultivate for analysts of comparative politics.

As I emphasised recently with my ‘Comparative Politics’ students at Swinburne Online, developing the skills to critically compare, consider and review positions and sources is essential for attaining and maintaining appropriate knowledge of different political systems. It’s also an important life skill. You might notice that across the community, many people don’t display these skills of critical evaluation and information hygiene (no matter what they might say about their “bullshit detectors”). That leaves them ripe for manipulation by all sorts of political actors.

Among those nefarious political actors, states employ a variety of tools to pursue their strategic objectives. Among the most potent of these are misinformation, disinformation, and psychological operations (psy-ops). These tactics are integral to what scholars’ term sharp power, a manipulative and coercive approach to influence that exploits vulnerabilities in open societies.

This article explores how these sharp power tools are used by state actors. It also presents a discussion-based learning activity to help students identify state-sponsored misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops, and evaluate counter-strategies to address information warfare as future International Relations professionals.

Elements of information warfare

Information warfare refers to the strategic use of information and communication to influence, manipulate, or disrupt the perceptions, behaviours, and decision-making processes of target audiences, often as a tool in geopolitical conflict.

Misinformation

In the context of state-sponsored information warfare within International Relations, misinformation refers to the deliberate dissemination of false or misleading information by a state actor with the intent to influence, manipulate, or disrupt the perceptions, behaviours, or decision-making processes of target populations or adversarial entities. This practice is often employed as part of a broader strategy to achieve political, military, or strategic objectives.

Unlike disinformation, which typically involves the fabrication of entirely false narratives, misinformation may also include the selective use of facts, omission of critical context, or distortion of information to create a misleading impression. It is a key tool in propaganda campaigns, psychological operations (psy-ops), and hybrid warfare, enabling states to sow confusion, erode trust in institutions, or destabilise rivals without engaging in direct conflict.

Examples of state-sponsored misinformation include:

- Spreading false narratives about election integrity to undermine confidence in democratic processes.

- Amplifying conspiracy theories to exacerbate societal divisions in rival states.

- Manipulating information about military capabilities to mislead adversaries during conflicts.

In International Relations, misinformation’s impact is amplified by digital platforms and social media, which allow rapid, widespread dissemination, often blurring the line between state actors and non-state proxies. Its use raises significant ethical and strategic concerns, particularly when it targets civilian populations or undermines the global information ecosystem.

Disinformation

In the context of state-sponsored information warfare within International Relations, disinformation refers to the deliberate creation and dissemination of false information by a state actor with the explicit intent to deceive and manipulate target audiences for strategic or political purposes. Unlike misinformation, which may involve unintentional inaccuracies, disinformation is crafted and deployed as part of a calculated effort to mislead.

Disinformation is a core tactic in propaganda and psychological operations (psy-ops), often used to achieve objectives such as destabilising adversarial states, influencing public opinion, or undermining trust in institutions. It frequently involves fabricating entirely false narratives, altering facts, or attributing fictitious actions or statements to individuals or entities.

Examples of state-sponsored disinformation include:

- Fabricating evidence of human rights abuses to justify military intervention or sanctions.

- Creating and distributing fake news stories to damage the reputation of political leaders or organisations in rival states.

- Orchestrating fake social media accounts or bots to spread false narratives during elections or geopolitical crises.

Disinformation campaigns are particularly effective in today’s digital age, where social media and online platforms enable rapid and widespread dissemination of falsehoods. The intentional nature of disinformation differentiates it from misinformation and raises profound ethical and legal concerns, particularly when it is used to manipulate democratic processes, incite violence, or destabilise international peace and security.

Psychological operations (psy-ops)

In the context of state-sponsored information warfare in International Relations, psychological operations (psy-ops) refer to the systematic and deliberate use of communication and behavioural manipulation techniques by state actors to influence the perceptions, attitudes, emotions, and decision-making of target audiences. The ultimate aim of psy-ops is to achieve strategic objectives by shaping the cognitive and psychological environment in which adversaries or populations operate.

Psy-ops are often deployed in conjunction with other tools of statecraft, such as military actions, economic policies, or diplomatic initiatives, as part of a comprehensive strategy. These operations may involve both overt and covert methods, including the dissemination of propaganda, exploitation of cultural or ideological divisions, and the use of misinformation or disinformation.

Examples of psy-ops in state-sponsored information warfare include:

- Dropping propaganda leaflets in conflict zones to demoralise enemy troops or encourage defection.

- Broadcasting messages via radio, television, or social media to influence public opinion in adversarial states.

- Launching targeted social media campaigns to amplify divisions within a rival country’s society.

Psy-ops are distinctive in their focus on psychological and emotional impacts rather than purely informational effects. By leveraging human vulnerabilities, such as fear, hope, or prejudice, psy-ops aim to create desired behavioural outcomes, ranging from compliance to unrest. While they can be effective tools of influence, their ethical implications, especially when directed at civilian populations or in peacetime contexts, remain deeply contested in International Relations.

Sharp Power

The concept of sharp power encapsulates how authoritarian regimes, in particular, use misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops to exert influence. Unlike soft power, which relies on attraction and persuasion, sharp power is inherently coercive, seeking to pierce, penetrate, and undermine democratic institutions, public discourse, and social cohesion. These tactics often exploit the freedoms inherent in open societies, such as free speech and access to information, turning these strengths into vulnerabilities.

By leveraging modern technologies, including artificial intelligence, social media algorithms, and big data analytics, states can execute sophisticated campaigns that blur the lines between influence and manipulation. Sharp power’s effectiveness lies in its ability to destabilise societies from within, making them more susceptible to external control.

Information warfare vs public relations and advertising

Information warfare, public relations (PR), and advertising all use communication to influence perceptions and behaviours, but they differ significantly in their goals, methods, and ethical considerations. Information warfare strategies are typically employed in military or geopolitical contexts to manipulate adversaries’ perceptions and emotions to achieve strategic objectives, often involving tactics such as misinformation and emotional manipulation.

Public relations, on the other hand, aims to build and maintain a positive reputation for an organisation or individual, relying on transparent communication strategies like press releases and social media campaigns to foster trust and goodwill. Advertising primarily focuses on promoting products, services, or ideas to encourage consumer action, using creative methods such as commercials and endorsements to appeal to the desires of specific demographics.

The methods used in information warfare, PR, and advertising also differ. Information warfare often involves covert tactics like spreading false narratives or exploiting vulnerabilities to destabilise the target, while PR relies on simple and direct communication strategies to manage public perception. Advertising employs storytelling and branding to influence consumer behaviour, using media campaigns and endorsements to appeal to the emotional and aspirational desires of consumers. Despite these differences, all three fields leverage an understanding of human psychology and mass communication tools to shape public opinion.

While information warfare, PR, and advertising share some similarities in their use of communication, they diverge significantly in purpose, methods, and ethical implications. Information warfare focuses on manipulation and destabilisation, whereas PR and advertising aim to influence audiences more transparently, whether to build trust or promote products. Each field uses mass communication tools, but the underlying intentions and ethical considerations differ, making them distinct despite their shared use of psychological influence.

Detecting deception in the fog of information warfare

Here I will draw on deception detection as a specific structured analytical technique, as articulated by Pherson and Heuer (2020, pp. 327-338) in their book Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis.

Deception detection is an analytical method that equips intelligence professionals with tools to identify and counter efforts by adversaries to manipulate their thinking or actions for strategic gain. By employing structured checklists, analysts can assess when deception might be occurring, determine its presence, and develop strategies to minimise its impact. As Pherson and Heuer (2020, p. 327) observe, effective deception often leaves no visible traces, while anticipating deception can lead to false alarms. This makes a systematic approach essential for maintaining a balance between scepticism and sound judgement.

Certain scenarios make deception more likely, such as when critical information is introduced at pivotal moments, comes from dubious sources, or challenges core assumptions and decisions. Successful deception often hinges on exploiting psychological tendencies like confirmation bias, over-reliance on initial impressions, or the tendency to favour familiar patterns. Adversaries may provide information that appears credible or valuable to reinforce these biases, making recipients less likely to question its authenticity.

While as analysts we can be generally aware that not all information can be trusted, grappling with the possibility of deception can overwhelm our analytical process. Structured frameworks for deception detection provide a way to manage these challenges.

Method for deception detection

By applying structured deception detection techniques, analysts can systematically examine the credibility of information and reduce the influence of cognitive errors. This approach ensures a more disciplined and objective analysis, even in the face of sophisticated attempts to mislead.

Pherson and Heuer’s (2020, pp. 335-338) method for deception detection emphasises the need for intelligence analysts to routinely consider the possibility of being misled, even in the absence of overt evidence. Recognising that effective deception often leaves no clear traces, the approach involves applying specific circumstances outlined in their “When to Use It” guidance and utilising structured checklists:

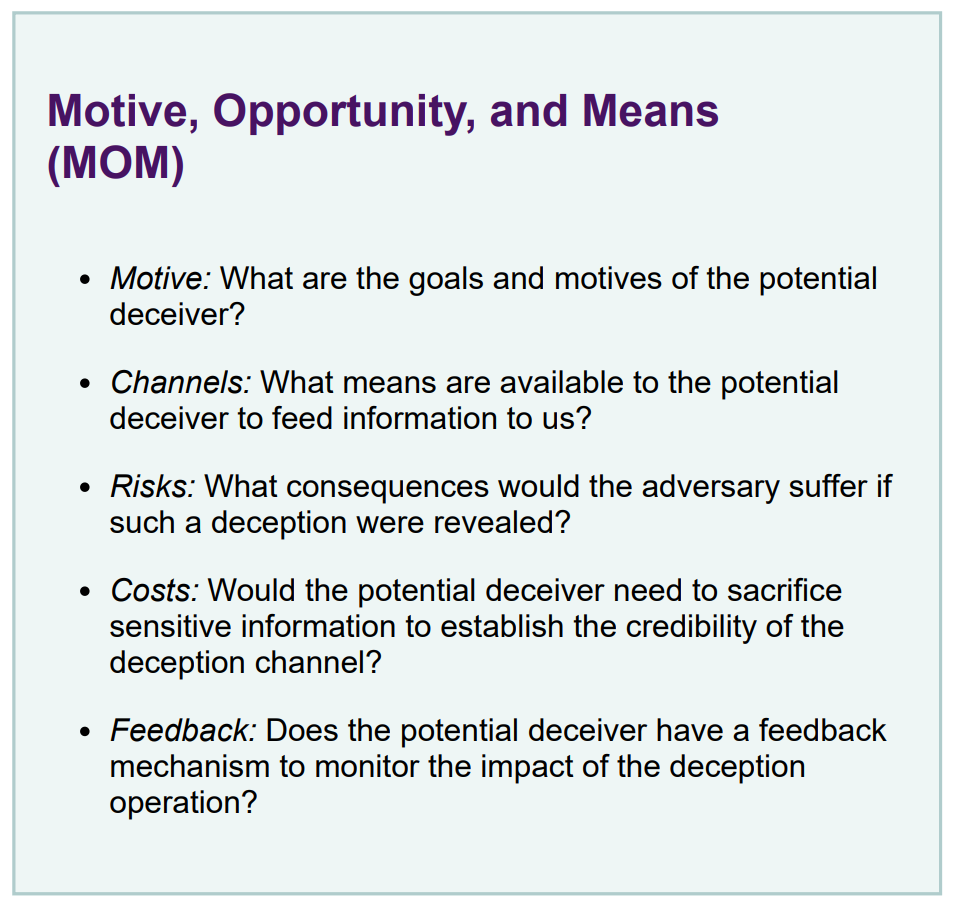

- Motive, Opportunity and Means (MOM).

- Past Opposition Practices (POP)

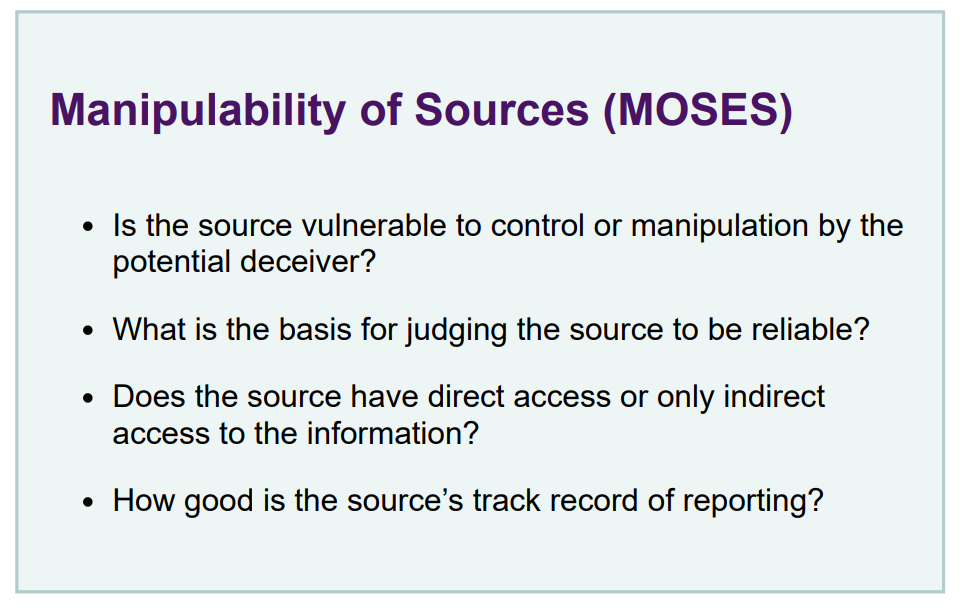

- Manipulability of Sources (MOSES).

- Evaluation of Evidence (EVE).

These tools help analysts systematically evaluate the likelihood of deception in a given scenario.

Furthermore, there are some key principles to guide analysts in anticipating and countering deception. These include avoiding reliance on single sources, validating human intelligence with material evidence, and being wary of information that aligns too neatly with existing biases. Analysts are also encouraged to scrutinise patterns of unreliable reporting and ensure hypotheses, including the possibility of deception, are explored thoroughly from the outset.

By combining structured checklists with these practical guidelines, we as analysts can enhance our ability to detect and respond to deception, maintaining a critical perspective while navigating the inherent challenges of ambiguous and incomplete data.

Learning activity

Students will work in groups of 3–4 and participate in a three-phase collaborative exercise involving research, analysis, and strategic planning. Each phase builds on the previous one to help students apply theoretical knowledge to real-world scenarios.

The goals or this activity are as follows:

- Comprehend: Gain a detailed understanding of the who, what, why, when, where, and how of misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops in International Relations.

- Analyse: Develop analytical skills to identify state-sponsored campaigns and distinguish between misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops in global discourses.

- Strategise: Propose counter-strategies to address information warfare from foreign adversaries as future International Relations (IR) professionals.

Part I: Decoding state-sponsored information warfare (30 minutes)

Objective: Learn the foundational elements (who, what, why, when, where, and how) of information manipulation by state actors.

a. Group assignment: Each group is assigned one state actor (e.g., one of the world’s great powers in China, Russia, or the United States, or another country of their choice). Engage with the Sharp Power Research Portal interactive map , published by the National Endowment for Democracy in Washington DC, to help you chose your case study.

b. Research and discussion: Groups use pre-provided materials (case studies, articles, or videos) to answer the following questions about their assigned state actor:

- Who: Which government agencies or proxies are responsible for information warfare?

- What: What are their primary objectives and methods?

- Why: Why are these tactics used? What strategic goals do they serve?

- When: In what contexts (e.g., elections, wars, crises) are these tactics most commonly employed?

- Where: Which regions, populations, or platforms are typically targeted?

- How: How are these tactics implemented, and what technologies are used?

c. Output: Groups create a concise summary (bullet points or visual map) to present to the class.

Part II: Analysing information warfare (30 minutes)

Objective: Develop analytical skills to identify misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops in real-world discourses.

a. Case study exercise: Groups are given real-world examples of suspicious content (e.g., news articles, tweets, videos, or official statements) related to international crises. These materials include both factual and manipulated examples to challenge critical thinking.

b. Identify key features: Groups analyse the content and identify…

- Indicators of misinformation (e.g., factual inaccuracies, lack of credible sources).

- Signs of disinformation (e.g., deliberate falsehoods, use of emotional appeals).

- Potential psy-ops strategies (e.g., targeting specific audiences, promoting division).

c. Output: Groups prepare a short analytical report highlighting…

- What type of information manipulation is present.

- The intent behind the campaign.

- Techniques used to influence perceptions or behaviours.

Part III: Developing counter-strategies (40 minutes)

Objective: Design strategies to counteract misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops as IR professionals, drawing on the Deception Detection Checklists—MOM, POP, MOSES and EVE—in Pherson and Heuer (2020, pp. 335-338).

a. Develop a role-play scenario: Each group assumes the role of an International Relations team advising their government or an international organisation. Groups are tasked with creating a counter-strategy to address a specific scenario involving information warfare (e.g., a disinformation campaign targeting an election or a psy-op attempting to destabilise a region).

b. Strategising for counter-measures: Groups use their understanding of the tactics to propose counter-measures, focusing on…

- Detection: Identifying the source and extent of the campaign.

- Mitigation: Public awareness campaigns, fact-checking initiatives, or media literacy programmes.

- Prevention: Technological solutions (e.g., AI for fake news detection), international cooperation, or policy recommendations.

c. Output: Groups present a 3-minute pitch of their counter-strategy to the class, simulating a high-level briefing.

Instructor’s role

The instructor facilitating this activity should facilitate the following for students to complete this activity:

- Provide initial context by delivering a brief lecture (10 minutes) on sharp power and the differences between misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops.

- Distribute curated case study materials for analysis.

- Guide discussions and encourage critical thinking by posing probing questions.

- Ensure groups stay focused and have the resources needed to complete each phase.

Expected learning outcomes

By the end of the activity, students will be able to:

- Have a strong understanding of sharp power and the use of misinformation, disinformation, and psy-ops in International Relations.

- Be able to critically analyse and identify manipulative information tactics.

- Demonstrate the ability to devise actionable counter-strategies relevant to real-world professional roles in IR.

This activity fosters collaborative learning and equips students with practical tools to navigate the complexities of information manipulation in International Relations.

Reference

Randolph H. Pherson and Richards J. Heuer Jr. (2021) Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis. 3rd Ed. (2024) “Sharp Power Book and Resource List

You must be logged in to post a comment.