- Paradigmatic change

- Comparing with other theories of systemic change

- Skills for evaluating systemic change

- Understanding of paradigms and paradigmatic change

- Historical and contextual analysis

- Critical thinking and scenario planning

- Recognising crises and anomalies

- Flexibility and adaptability

- Cultural awareness and understanding of global movements

- Diplomatic innovation and conflict management

- Leadership in times of transition

- Theoretical and practical integration

- Learning activity: Analysing systemic change

- Summary

- References

Understanding systemic change is fundamental to the study of International Relations, as it offers insights into how societies, political systems, and international frameworks evolve over time. In this article, drawing upon Raymond F. Smith’s application of Thomas Kuhn’s concept of paradigm shifts in his book The Craft of Political Analysis for Diplomats as a starting point, I explore paradigmatic change, state failure, revolutions, and regime change as distinct yet interconnected theories of transformation, each providing unique perspectives on how crises and contradictions within systems catalyse change.

Through the accompanying practical learning activity, this article equips students with the tools to recognise indicators of systemic change, evaluate their implications, and develop the skills necessary for navigating systemic transformation of the broader international system. The accompanying learning activity invites students to apply these frameworks to a real-world case study, fostering a deeper understanding of systemic change and its complexities.

Paradigmatic change

In The Craft of Political Analysis for Diplomats, Raymond F. Smith explores the dynamics of political change, drawing upon Thomas Kuhn’s concept of “paradigm shifts” from The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Smith applies Kuhn’s theory to political analysis, arguing that societal change does not follow a linear progression, but rather occurs through revolutionary shifts.

Just as scientific paradigms face crises when they can no longer accommodate anomalies, political systems can experience crises when contradictions within the existing paradigm accumulate beyond its capacity to adapt. These contradictions eventually reach a tipping point, triggering a transformative shift to a new social structure.

Central to Smith’s argument is the concept of dialectics, which underpins his interpretation of societal change. Societies are inherently imperfect, and these imperfections, or contradictions, accumulate over time. Once these contradictions become overwhelming, they catalyse a revolutionary change, akin to a scientific revolution in Kuhn’s terms.

Comparing with other theories of systemic change

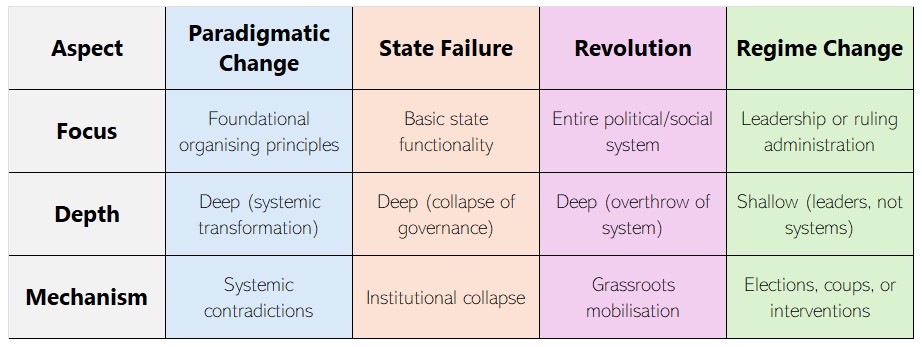

The concept of paradigmatic change, as articulated in Raymond F. Smith’s excerpt, offers a framework for understanding systemic transformations in societal organisation by borrowing Thomas Kuhn’s ideas from the philosophy of science. This theory can be compared and contrasted with theories of state failure, revolutions, and regime change, all of which explore systemic transformation but differ in emphasis, underlying assumptions, and analytical focus.

State failure, revolutions, and regime change

Theories of state failure, revolutions, and regime change offer overlapping yet distinct frameworks for understanding systemic political transformations, each emphasising different causes, dynamics, and consequences.

State failure is frequently defined as the collapse of legitimate authority and institutional functionality, with scholars such as Rotberg (2004) highlighting the breakdown of governance and public service delivery, while Goldstone et al. (2000) of the State Failure Task Force identify demographic and economic pressures as critical precursors.

Theories of revolution, exemplified by Skocpol (1979), attribute upheaval to structural factors such as state fragility and class conflicts, whereas Tilly (1978) underscores the importance of collective action and political opportunities in shaping revolutionary outcomes.

In contrast, regime change theories, as articulated by Huntington (1991), examine transitions from authoritarianism to democracy, focusing on cultural and international influences, with Linz and Stepan (1996) addressing the processes of institutional consolidation and elite bargaining crucial for successful transitions.

While each theory maintains a distinct focus, they converge in recognising the complex interplay of institutional weaknesses, social mobilisation, and external forces in driving systemic political change.

Key Similarities

All four frameworks—paradigmatic change, state failure, revolutions, and regime change—are concerned with identifying moments of significant systemic crisis within societal or political systems. In paradigmatic change, a “crisis” arises when contradictions within the dominant societal paradigm become irreconcilable, necessitating the emergence of a new paradigm. Similarly, state failure theory focuses on the collapse of institutional capacity and legitimacy, while revolution theories study societal breakdowns that culminate in the overthrow of existing power structures. Regime change, while narrower in scope, often occurs against the backdrop of systemic crises that precipitate a leadership or administrative shift.

Both paradigmatic change and revolutions view crises as catalysts, as moments that break the continuity of “normalcy.” Smith’s idea of qualitative change echoes moments of revolutionary fervour where existing norms collapse, and new political, social, or economic systems emerge. Regime change, in contrast, is more limited in its focus on leadership or administrative shifts, though it too can be spurred by crises, such as economic collapse or military defeat.

Theories of state failure and paradigmatic change both emphasise structural weaknesses or contradictions within systems. For paradigmatic change, these are “anomalies” or problems that cannot be reconciled within the existing paradigm. In state failure, these weaknesses manifest as the erosion of state legitimacy, economic dysfunction, or an inability to meet basic societal needs. Revolution theories and regime change likewise highlight structural weaknesses but often frame them through the lens of collective action or elite decisions.

Key Differences

The distinctions between paradigmatic change, state failure, revolutions, and regime change lie in their conceptual scope, agents of change, outcomes, and timescales.

On the contrast of conceptual scope, paradigmatic change broadly addresses shifts in the “organising paradigm” of a society, encompassing political, economic, and cultural dimensions, and extending beyond the state to societal norms, values, and systems of thought. In contrast, state failure narrows its focus to the collapse of the state as a governing institution, highlighting its inability to exercise authority, maintain territorial integrity, or deliver services. Revolutions, however, concentrate primarily on political change, specifically the overthrow of ruling elites or regimes, often driven by social movements, class struggles, or ideological shifts. Regime change, by comparison, refers to the replacement of one governing administration or leadership with another, without necessarily altering the underlying political, economic, or societal paradigm.

The agents driving these changes also differ. Paradigmatic change emerges from the internal contradictions within dominant frameworks and lacks predefined agents, unfolding as a structural and systemic process. State failure emphasises external and internal pressures, such as economic shocks or conflict, often attributing agency to elites, insurgents, or external powers. Revolutions, on the other hand, identify specific actors, such as oppressed classes or revolutionary leaders, who instigate systemic change through collective action. Regime change typically involves political or military actors, including domestic elites or foreign powers, operating within the existing systemic framework.

The outcomes of these processes are equally varied. Paradigmatic change leads to the emergence of a new societal framework or paradigm, potentially redefining norms, institutions, and values, though this may or may not involve violence or overt political collapse. State failure often results in chaos, fragmentation, or the emergence of new power centres, with no inherent promise of a coherent new system. Revolutions explicitly aim for political and social reorganisation, frequently establishing new regimes or political orders, though outcomes depend on post-revolutionary dynamics. Regime change, by contrast, results in leadership transitions while retaining the systemic framework, and while it may coincide with systemic crises, it does not inherently signify structural transformation.

These processes also unfold over different timescales. Paradigmatic change occurs gradually, often over decades or centuries, as long-term contradictions manifest in crises. State failure is typically abrupt, triggered by immediate crises such as war or economic collapse. Revolutions occupy a middle ground, stemming from long-term grievances but often catalysed by short-term crises. Regime change, however, is usually rapid, particularly in the case of coups or foreign interventions, and is confined to short-term political transitions.

Skills for evaluating systemic change

Students of International Relations, particularly those aspiring to become International Relations professionals, should develop a set of specific knowledge areas and skills to effectively recognise and navigate paradigmatic change in the international system. Based on Raymond F. Smith’s analysis of societal and political change in The Craft of Political Analysis for Diplomats, students should work at developing the following key competencies:

Understanding of paradigms and paradigmatic change

Aspiring International Relations professionals must grasp the concept of paradigms as systems of thought that shape societal and political organisation. They should study how paradigms function in both scientific and political contexts, understanding how established systems of governance, ideologies, and international norms can become outdated or incapable of addressing emerging challenges.

Key to this understanding is the recognition that political systems are not static and may experience crises when their foundational assumptions or methods no longer accommodate evolving realities. Students should also become familiar with the broader theories of societal and political change (e.g. paradigmatic change, state failure, revolution, and regime change).

Historical and contextual analysis

A deep knowledge of historical shifts in the international system is essential. International Relations professionals must understand how past events have shaped the current global order. By analysing historical patterns and crises, diplomats can identify recurring contradictions in the international system that may signal the need for change. Similarly, an understanding of the specific social, economic, and political contexts of different states is crucial for recognising when contradictions in international relations may lead to systemic shifts.

Critical thinking and scenario planning

International Relations professionals must cultivate critical thinking skills to analyse international developments in a nuanced and objective manner. This involves questioning the status quo and examining existing paradigms for their underlying assumptions, contradictions, and limitations.

Scenario planning is an essential skill, enabling International Relations professionals to anticipate potential shifts and crises. Scenario planning helps diplomats envision how different factors—such as technological advancements, geopolitical power shifts, or environmental crises—could catalyse a paradigm shift in a given state and even across the international system.

Recognising crises and anomalies

Smith’s passage highlights the importance of recognising when systemic anomalies—events or trends that contradict the expectations of the existing paradigm—begin to accumulate. International Relations professionals must develop the ability to spot these anomalies early, whether they manifest in changes in global trade patterns, rising nationalism, or new forms of global cooperation or conflict. By identifying early signs of crisis, IR adepts can better prepare for potential shifts and understand when the international system may be approaching a tipping point.

Flexibility and adaptability

In times of systemic change, professional practices must be flexible and adaptable. For example, diplomats need to be able to navigate rapidly shifting landscapes, especially in the face of uncertainty or ambiguity. Training in adaptive diplomacy—methods of negotiation and engagement that are fluid and responsive to changing circumstances—is critical.

International Relations professionals should learn to remain open to new approaches to global governance, recognising that traditional methods of diplomacy and engagement may no longer be appropriate in a rapidly evolving international system.

Cultural awareness and understanding of global movements

The ability to understand and respond to the diverse cultural, political, and social forces that shape international relations is indispensable. International Relations professionals must be attuned to the rise of new global movements, including populist movements, environmental activism, and shifts in regional power dynamics. An awareness of how these movements challenge the existing global order will help IR professionals navigate the tensions between old and new paradigms.

Furthermore, understanding the role of non-state actors, such as multinational corporations, NGOs, and transnational movements, is increasingly important in a world where state-centric paradigms are being challenged.

Diplomatic innovation and conflict management

International Relations professionals must be skilled in managing conflicts that arise during periods of systemic crisis. This involves not just traditional conflict resolution, but also the ability to innovate in diplomacy by suggesting and implementing new frameworks for cooperation, security, and trade. They should be able to innovate novel forms of engagement and guide international negotiations towards consensus, even when existing norms and structures seem inadequate to address new global challenges.

Leadership in times of transition

Leadership during periods of paradigm shift is critical. International Relations professionals should learn how to provide leadership and act as stabilising forces in the midst of uncertainty. This includes the ability to propose and champion new approaches to diplomacy and engagement that align with the emerging new global order. Developing strong leadership skills, particularly in multilateral contexts, will help International Relations professionals to influence the direction of change.

Theoretical and practical integration

To navigate systemic change, students of International Relations should integrate theoretical knowledge with practical skills. This includes studying international law, political theory, economics, and regional studies while also honing practical skills in negotiation, diplomacy, and crisis management. The ability to apply theoretical frameworks to real-world challenges will be crucial in identifying potential shifts and responding effectively.

Learning activity: Analysing systemic change

This learning activity invites undergraduate student of International Relations to explore the dynamics of systemic change through the lenses of paradigmatic change, state failure, and revolutions. Students will select a country as a case study and critically analyse its historical and contemporary political-economic system, integrating the key skills for evaluating systemic change as listed above.

Intended learning outcomes

This activity aims to develop students’ analytical skills, deepen their understanding of systemic change, and foster the ability to think critically about complex political dynamics in the international system.

Specifically, these are the desired outcomes of this activity:

- Depth of understanding of paradigmatic change, state failure, revolutions, and regime change.

- Ability to apply theoretical frameworks to empirical case studies with creativity and adaptability.

- Demonstrate understanding of the history, political-economic context and culture of their chosen case study state.

- Quality of argumentation, use of supporting evidence, and clarity of communication.

- Critical analysis and engagement with scholarly literature.

Instructions

This learning activity should be completed as a combination of individual student research and in-class discussion-based collaboration in groups of 3-4 students, leading to the submission by each student of a research essay documenting their findings.

Part I: The dominant organising paradigm

Individual research: Identify the dominant organising paradigm of the chosen country. Consider the foundational principles, norms, and institutions that underpin the country’s political, economic, and social structures.

In groups: Discuss how this paradigm influences governance, societal priorities, and international engagement.

Part II: Irreconcilable problems within the paradigm

Individual research: Analyse the contradictions or anomalies inherent in the country’s dominant paradigm. These may include economic inequalities, political corruption, environmental degradation, or cultural conflicts. Draw connections between these issues and broader systemic weaknesses, using examples to illustrate how they challenge the paradigm’s sustainability.

In groups: Compare, contrast and catalogue the contradictions and systemic weaknesses you have identified.

Part III: Theories of systemic transformation

Individual research: Examine your case study state from the perspective of each theory of systemic transformation…

- Apply the theory of paradigmatic change to examine how unresolved contradictions might lead to a paradigm shift in the case study country. Identify potential catalysts for this shift.

- Use state failure theory to explore whether the country’s challenges might erode institutional capacity and legitimacy, potentially leading to governance collapse.

- Evaluate whether revolutionary dynamics are present or could emerge, considering factors like social movements, economic crises, or political repression.

- Explore whether regime change via military intervention from another state actor is a possibility for your chosen state.

In groups: Share and critically evaluate your individual findings as a group.

Part IV: Comparative analysis

In groups: Compare the potential outcomes of paradigmatic change, state failure, and revolution in the chosen country. Which pathway seems most plausible given the current context? Why? Assess the role of external forces, such as globalisation, international conflict, or climate change, in shaping these dynamics. Document your findings.

Part V: Research essay

Individual research: Students should compile a 2,000-word research essay that documents their key findings from

Summary

While paradigmatic change, state failure, revolutions, and regime change all examine systemic transformation, they differ significantly in scope, causation, and outcomes. Paradigmatic change offers a holistic view of societal evolution driven by internal contradictions, state failure focuses on the collapse of governance, revolutions emphasise political overthrow and reorganisation, and regime change addresses leadership transitions without systemic change.

For students of International Relations, understanding these frameworks is crucial for analysing both gradual societal shifts and sudden political upheavals in the international system. Each theory provides valuable insights into the complex dynamics of change, highlighting different dimensions of societal and political transformation.

References

Call, C. T. (2008). The fallacy of the ‘failed state’. Third World Quarterly, 29(8), 1491-1507.

Foran, J. (2005). Taking Power: On the Origins of Third World Revolutions. Cambridge University Press.

Goldstone, J. A. (1991). Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World. University of California Press.

Goldstone, J. A. et al. (2000). State failure task force report: Phase III findings. Political Instability Task Force.

Goodwin, J. (2001). No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945-1991. Cambridge University Press.

Gros, J.-G. (1996). Towards a taxonomy of failed states in the New World Order: Decaying Somalia, Liberia, Rwanda and Haiti. Third World Quarterly, 17(3), 455-471.

Huntington, S. P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Linz, J. J., & Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rotberg, R. I. (2004). When States Fail: Causes and Consequences. Princeton University Press.

Skocpol, T. (1979). States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China. Cambridge University Press.

Smith, R. F. (2013). The Craft of Political Analysis for Diplomats. Potomac Books.

Tilly, C. (1978). From Mobilization to Revolution. Addison-Wesley.

Whitehead, L. (2020). Regime change. In The SAGE Handbook of Political Science (Vol. 3, pp. 867-883). SAGE Publications.

Zartman, I. W. (1995). Collapsed States: The Disintegration and Restoration of Legitimate Authority. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.