- What are primary sources?

- Types of primary sources cited in IR research

- Government documents and official records

- International organisation records

- Non-governmental organisation (NGO) reports

- Media reports and journalism

- Personal accounts and correspondence

- Statistical and quantitative data

- Historical archives

- Interviews and oral histories

- Legal documents

- Cultural and propaganda materials

- Fieldwork and direct observations

- Digital and social media content

- Evaluating primary sources

- Learning activity

- Summary

- Suggested resources

In International Relations, the ability to critically analyse sources is fundamental to understanding global events, decisions, and power dynamics. Primary sources offer unfiltered insights into the actions and motivations of key actors. However, their effective use requires a forensic approach in evaluating their strengths, limitations and applicability. This blog explores how students can develop these critical skills.

Beyond evaluating individual sources, the practice of source triangulation takes research one step further. By integrating diverse perspectives, triangulation enables researchers to identify patterns, mitigate biases, and draw more robust conclusions.

This article also introduces a two-part learning activity designed to teach students the principles of primary document analysis and source triangulation, equipping them with the practical epistemological skills to conduct their IR research with greater confidence and precision.

What are primary sources?

A primary source is an original document, record, or artefact that provides direct evidence about an event, phenomenon, or subject of study. In International Relations, primary sources are materials created by actors directly involved in global affairs, such as governments, international organisations, non-governmental organisations, media, or individuals. These sources offer unfiltered insights into policies, decisions, and events, making them essential for analysing state behaviour, global governance, and transnational dynamics.

These sources allow researchers to analyse state behaviour, diplomatic negotiations, and international events as they were documented or experienced at the time, offering authenticity and immediacy. They also enable the investigation of power dynamics, institutional processes, and the motivations behind policies. Moreover, primary sources serve as the foundation for building rigorous, evidence-based arguments and contribute to nuanced interpretations of complex international issues.

Types of primary sources cited in IR research

International Relations researchers often engage with a variety of primary sources depending on their research questions, theoretical frameworks, and methodological approaches. Below is an overview of the most common types of primary sources encountered in IR research, including types of documents encountered in each category, a summary of their uses, limitations and when they are best utilised as reliable evidence, and illustrative examples from my own research.

Government documents and official records

Document types: These include diplomatic correspondence (e.g., embassy cables, treaties, and agreements); legislative records (e.g., parliamentary debates, congressional reports, or UN resolutions); policy papers from government agencies (e.g., white papers, national security strategies); and official speeches and statements by political leaders or diplomats.

Uses: Provide direct insights into official state policies, decision-making processes, and diplomatic communications. Essential for studying state behaviour and formal international agreements.

Limitations: May reflect political bias or propaganda; access can be restricted, especially for classified material. They often lack the perspectives of non-state actors.

Best utilised: When studying state policies, treaty negotiations, or the formal positions of governments in international forums.

Ben’s examples: I drew on diplomatic cables in my paper (with Lisa Tuck) on climate change in the WikiLeaks ‘Cablegate’ archive, and on congressional reports, white papers and national security strategies in my research into Korean Peninsula nuclear diplomacy.

International organisation records

Document types: These include meeting minutes, reports, and resolutions from organisations like the United Nations, World Trade Organisation, or NATO; and data sets produced by organisations (e.g., IMF financial statistics or World Bank development indicators).

Uses: Offer data and analyses on global governance, policy implementation, and international cooperation. Useful for understanding institutional processes and norms.

Limitations: Reflect the biases or political agendas of member states and leadership. Resolutions and reports may use ambiguous language to accommodate diverse interests.

Best utilised: In research on multilateral diplomacy, global governance, or international law.

Ben’s examples: I have analysed UN Security Council resolutions in my research into DPRK-related economic sanctions, and UN treaty documents in my research into North Korea and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Non-governmental organisation (NGO) reports

Document types: These include advocacy reports and studies conducted by NGOs such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, or Greenpeace; and fieldwork accounts and situational reports from conflict or crisis zones.

Uses: Provide on-the-ground data and perspectives often overlooked by governments and international organisations. Highlight human rights, environmental, or humanitarian concerns.

Limitations: May be advocacy-driven and lack neutrality. Data collection methods may vary in rigour and scope.

Best utilised: When exploring issues of human rights, environmental activism, or the role of civil society in international politics.

Ben’s examples: NGO reports from agencies working in-country in North Korea were pivotal in my research into climate change adaptation in the DPRK.

Media reports and journalism

Document types: These include articles, interviews, and investigative pieces from reputable news outlets; transcripts of press conferences or public debates.

Uses: Offer contemporary accounts of events, public opinion, and media framing. Useful for tracking the evolution of crises or international incidents.

Limitations: Subject to editorial bias, sensationalism, and inaccuracies. Over-reliance on specific outlets can skew analysis.

Best utilised: For studying the role of public opinion, media framing of international events, or real-time developments in crises.

Ben’s examples: Staying up-to-date on events in Northeast Asia related to my research was made possible by following niche media sites such as NK News, 38 North, Sino:NK, along with news from mainstream media organisations. These media sources were particularly useful to me when providing immediate commentary on breaking events, as in my articles in The Conversation.

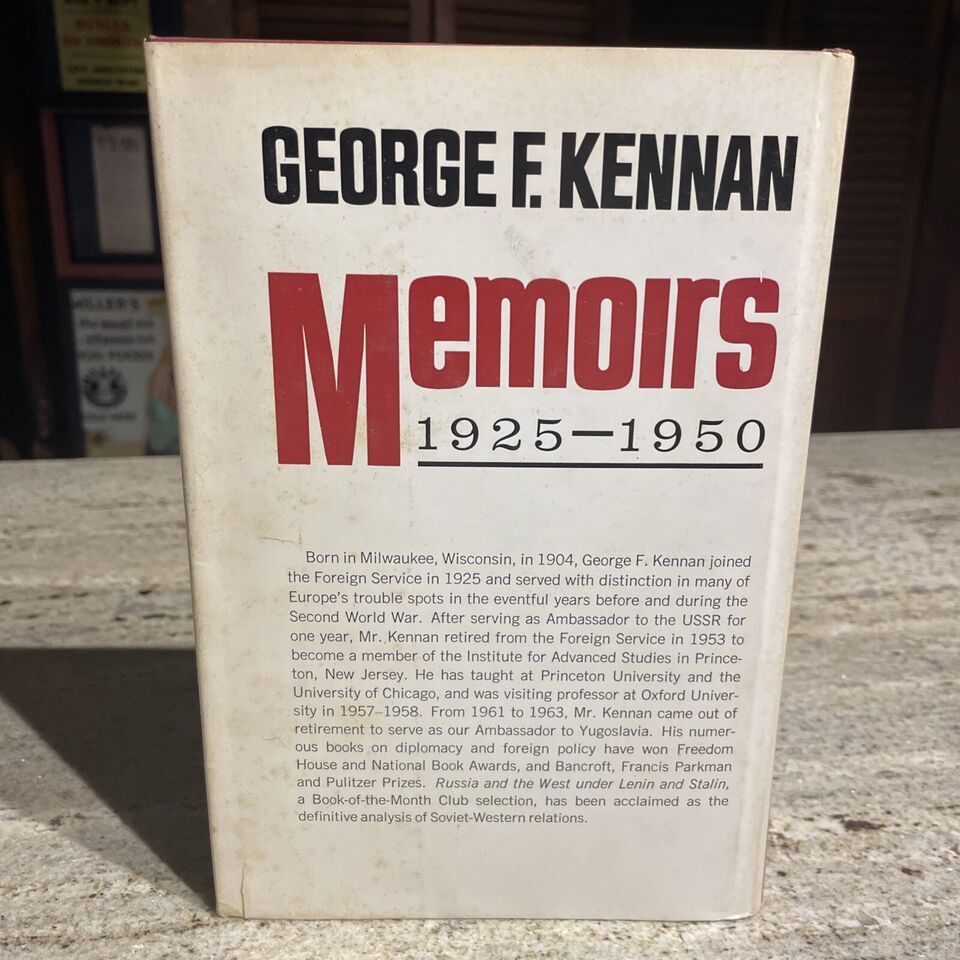

Personal accounts and correspondence

Document types: These include memoirs and autobiographies of policymakers, diplomats, or political leaders; private correspondence (e.g., letters or emails between key actors in international negotiations); and diaries and other personal reflections.

Uses: Provide intimate insights into decision-making processes, individual motivations, and the human dimension of diplomacy or conflict.

Limitations: Subjective and potentially selective in what they reveal. Authorship biases and limited availability can affect reliability.

Best utilised: In biographical or leadership studies, or when exploring the personal dimensions of high-stakes decision-making.

Ben’s examples: Personal accounts such as Going Critical: The First North Korean Nuclear Crisis, by American diplomats involved in those negotiation—Joel Wit, Daniel Poneman and Robert Gallucci—were an important source in my work into the motivations for North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

Statistical and quantitative data

Document types: These include economic indicators, trade data, and demographic statistics from sources like the World Bank or national statistical agencies; and conflict data sets (e.g., Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Correlates of War).

Uses: Enable empirical analysis of trends in trade, conflict, or development. Provide a foundation for quantitative models and comparative studies.

Limitations: May lack contextual nuances or be influenced by methodological choices. Accuracy depends on the quality of data collection.

Best utilised: For macro-level analyses of trends in international trade, conflict, or development.

Ben’s examples: In my own research, I drew on North Korean trade statistics published by the South Korea’s Ministry of Unification and NK Pro in research papers on North Korea’s parallel economies and (with Jay Song) migration patterns in the DPRK.

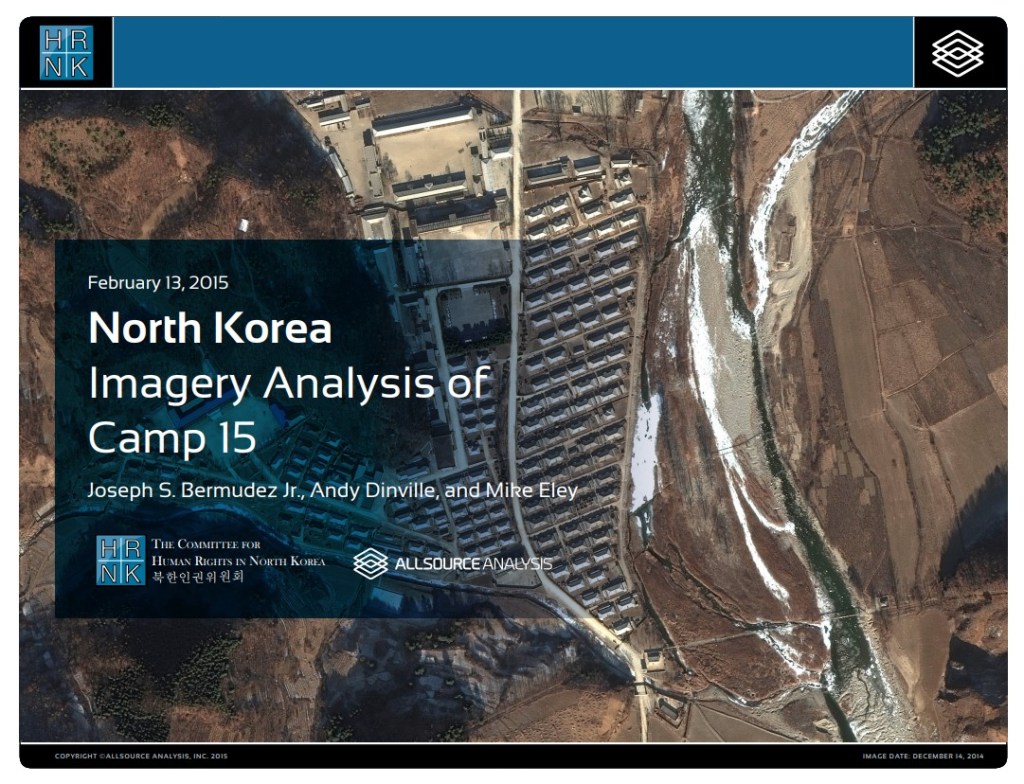

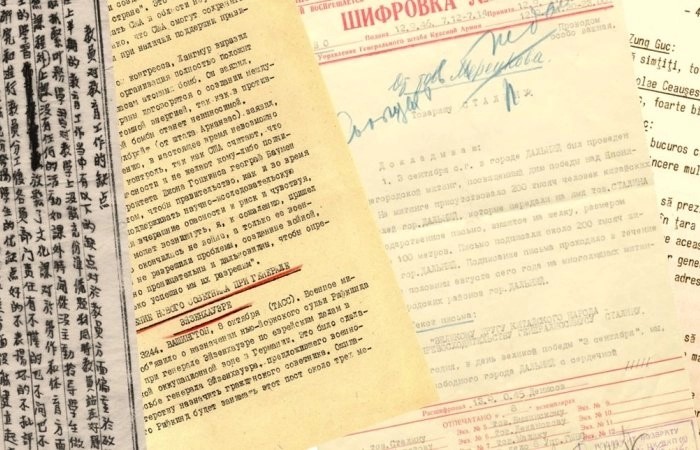

Historical archives

Document types: These include archival materials housed in national libraries, diplomatic archives, or academic institutions; and declassified documents (e.g., FOIA requests in the US, Cabinet Papers in the UK).

Uses: Offer rich, detailed insights into past events and decisions, including declassified documents that shed light on state actions.

Limitations: Access can be limited by classification laws or national security concerns. Interpretation may be challenging due to incomplete records.

Best utilised: For historical case studies or when analysing long-term trends in diplomacy or foreign policy.

Ben’s examples: The North Korea International Documentation Project, published by the Wilson Center, in an archive of official documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that has proved invaluable to backgrounding my research and for developing teaching content for my undergraduate subject Contemporary Politics of Northeast Asia.

Interviews and oral histories

Document types: These include interviews with policymakers, practitioners, and stakeholders; and oral history projects documenting past events through the recollections of participants.

Uses: Capture first-hand experiences and retrospective interpretations of events, often filling gaps in the written record.

Limitations: Subject to memory biases, selective recall, and potential self-serving narratives by interviewees.

Best utilised: For qualitative studies involving policymakers, stakeholders, or participants in specific events.

Ben’s examples: I conducted participatory-action research into the global permaculture movement, based on interviews with permaculture practitioners from around the world.

Legal documents

Document types: These include court rulings from international tribunals (e.g., International Court of Justice or International Criminal Court); and legal opinions and treaty interpretations.

Uses: Provide authoritative interpretations of international law, treaty obligations, and judicial decisions.

Limitations: Often complex and technical, requiring specialised legal knowledge. May reflect political compromises or differing interpretations.

Best utilised: In research on international law, treaty compliance, or the outcomes of international legal disputes.

Ben’s examples: I have made use of treaty interpretations of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in my work on North Korea’s participation in the UNFCCC, and arbitration rulings from the International Court of Justice on the South China Sea in teaching my subject Security in the Indo-Pacific.

Cultural and propaganda materials

Document types: These include political cartoons, posters, and propaganda materials; and cultural artefacts reflecting public attitudes toward international events or relations.

Uses: Reveal state narratives, ideological underpinnings, and public mobilisation efforts.

Limitations: Highly biased and designed to persuade rather than inform. Interpretation requires careful contextualisation.

Best utilised: When studying state propaganda, nationalism, or public diplomacy.

Ben’s examples: I have not cited propaganda and cultural artefacts specifically (although official North Korean media fits in the “propaganda” category), however I have used these in teaching activities in my subject Contemporary Politics of Northeast Asia.

Fieldwork and direct observations

Document types: These include ethnographic field notes from regions experiencing conflict or undergoing significant political transitions; and participant observations from diplomatic summits, peacebuilding efforts, or international conferences.

Uses: Provide real-time, context-rich insights into local conditions, practices, and interactions.

Limitations: Highly resource-intensive and may involve subjective interpretations by the researcher.

Best utilised: In ethnographic or practice-based research, particularly in conflict zones or transitional societies.

Ben’s examples: I keep a diary of field observations on all of my overseas research trips. The best example of this is documented in A “Strong and Prosperous Country”? Field Report from North Korea.

Digital and social media content

Document types: These include content from platforms like Twitter, Facebook, or Telegram, especially in studies of public diplomacy, propaganda, or cyberconflict; and official government accounts on social media.

Uses: Capture real-time public discourse, state communications, and grassroots movements. Useful for analysing propaganda, disinformation, or digital diplomacy.

Limitations: Prone to misinformation, echo chambers, and limited verifiability. Large volumes of data can complicate analysis.

Best utilised: For studies of public diplomacy, cyberconflict, or social media’s role in shaping international narratives.

Ben’s examples: Official announcements made on social media have become increasingly important over the past decade, at no time more so than during Donald Trump’s first presidency in the US. Trump’s regular posts on Twitter about Korean Peninsula nuclear diplomacy were an important part of that diplomatic process, as documented in my commentary on that topic in 2018-2019.

Evaluating primary sources

Evaluating primary sources is a cornerstone of rigorous International Relations research, enabling students to critically assess the authenticity, credibility, and relevance of evidence while addressing inherent limitations and ensuring sources are appropriately contextualised within their research framework.

International Relations researchers face several challenges when evaluating primary sources. One of the primary obstacles is access, as many key documents, such as diplomatic archives, government reports, or classified materials, are restricted or not readily available to the public. This limits researchers’ ability to gather a complete set of primary evidence.

Another significant challenge is bias and reliability. Official documents, such as government reports or media sources, often reflect the political or ideological stance of the entity that produced them, which can skew the information presented. Researchers must critically assess these biases and consider how they may shape the source’s content and perspective.

Additionally, interpreting primary sources can be difficult, as the meaning of a document is highly dependent on its context—historical, political, or cultural—which researchers must fully understand in order to avoid misinterpretation. The framing of the source also plays a crucial role in determining its implications, and any gaps in knowledge or understanding can lead to flawed conclusions.

This section provides a comprehensive checklist to examine the strengths, limitations, and best use of primary sources, alongside a discussion on the research practice of source triangulation to enhance research validity.

Student resource: Checklist for evaluating primary sources

By framing evaluation in terms of strengths, limitations, and best use, students can develop a critical understanding of primary sources, ensuring they are utilised effectively and appropriately in International Relations research.

Strengths: What Makes This Source Valuable?

- Authenticity: Is the source an original document or account providing direct evidence? Is the source official (e.g., government or organisational records) or unofficial (e.g., personal accounts, media reports)?

- Credibility: Who created it, and what is their authority or expertise? Was it created by a reliable or authoritative actor (e.g., government, NGO, expert)?

- Unique insights: Does it offer information or perspectives unavailable in other sources?

- Relevance: How directly does the source address your research question or topic?

- Specificity: Are the details precise, well-documented, or supported by data?

Limitations: What Are the Weaknesses or Challenges?

- Bias and perspective: Does the source reflect a particular bias (e.g., political, ideological, cultural)? Whose perspective does the source represent (e.g., state, non-state actor, individual)? Are certain perspectives excluded or marginalised?

- Purpose and intent: Why was the source created, and for what audience?Was the source created to inform, persuade, or mislead? Does its purpose (e.g., propaganda, advocacy) affect its objectivity? Does the purpose of the source (e.g., informational, persuasive, propagandistic) affect its content or tone?

- Completeness: Is the evidence specific, detailed, and verifiable?Is the source missing key information due to redactions, translation issues, or access restrictions? Are there ambiguities, contradictions, or gaps in the evidence?

- Contextual constraints: What was the historical, political, or social context at the time of its creation?Does the source reflect the specific conditions or limitations of its time and place? Is it outdated or no longer relevant to current contexts?

- Accessibility: Is the source complete, or are there redactions or missing sections? Are there classification, access, or translation issues that affect its usability? Are the data or observations in the source time-sensitive or outdated?

- Methodological considerations: Was the source produced using a systematic and transparent method (e.g., statistical data, NGO reports)? Are the methodologies or assumptions underpinning the source clear and valid? How might the method of data collection or reporting influence the findings?

- Ethical considerations: Are there ethical concerns in using this source (e.g., privacy, consent)? Does using the source require careful contextualisation to avoid misrepresentation or harm?

Best Use: When and How Should This Source Be Used?

- Research focus: Does the source align with the specific aims of your research (e.g., state behaviour, humanitarian issues)? Is it most useful for qualitative insights, quantitative analysis, or historical interpretation?

- Complementarity: How does this source enhance or balance other types of evidence? Does it help corroborate findings from secondary sources or other primary sources?

- Case study potential: Is the source well-suited for detailed examination as part of a broader case study?

- Triangulation: Can the information in the source be corroborated by other primary or secondary sources to reduce bias and increase validity? How does the source contribute to a broader understanding of the issue when triangulated with others?

Source triangulation

In International Relations research, primary sources are best utilised as one piece in a broader mosaic of corroborating evidence. Constructing this broader mosaic of evidence is called source triangulation. In my own research on North Korea (for example, Habib 2015), triangulation of sources was essential due to the limitations of access to the DPRK and the ambiguity surrounding any one piece of evidence (see also Tan 2019).

Source triangulation is the process of using multiple types of sources or perspectives to examine a phenomenon, ensuring a more robust, accurate, and credible analysis (Obar 2021). By drawing on a range of materials, researchers can identify patterns, validate findings, and reduce the risk of biases or errors in their conclusions. This technique is fundamental to enhancing the validity and depth of research, particularly in complex and multifaceted fields such as International Relations.

The primary purpose of source triangulation lies in its ability to increase the validity of findings by confirming the consistency and reliability of data across different sources (Kern 2018; Hales 2010). It minimises the influence of individual source biases—whether ideological, political, or methodological—while enabling a comprehensive analysis that incorporates diverse perspectives, such as those of state and non-state actors or local and international viewpoints. Moreover, triangulation aids in identifying contradictions, prompting further investigation where discrepancies arise, and enhances the overall credibility of findings, making them more persuasive to peers, policymakers, and other stakeholders.

The process of source triangulation involves several key steps:

- Alignment: Researchers must identify relevant sources that align with the research question and offer complementary perspectives. This might include primary and secondary sources, as well as a mix of quantitative and qualitative data.

- Categorising: These sources are then categorised based on their origin—for instance, whether they stem from state entities, international organisations, civil society, or individuals. Researchers should also differentiate between direct evidence, such as archival records, and interpretative commentary, such as journalistic analysis.

- Comparison and cross-checking: Once sources are organised, the process moves to comparing and cross-checking the information they provide, analysing whether perspectives align or diverge. Patterns of agreement can reinforce the credibility of findings, while inconsistencies demand deeper scrutiny.

- Relate to context: Contextualising sources is equally vital, requiring an assessment of each source’s purpose, audience, and potential biases, as well as consideration of the temporal context, as newer evidence may challenge earlier conclusions.

- Integration: Findings from triangulated sources are integrated into a coherent narrative, highlighting areas of convergence and acknowledging any points of divergence as opportunities for further exploration or debate. Where discrepancies persist, additional methods such as interviews, field observations, or further data analysis can help verify or clarify the findings.

Source triangulation is a useful method for ensuring rigour and reliability in International Relations research, and particularly in a field as dynamic and ambiguous as my speciality in North Korean Studies.

Learning activity

To acculturate students into the art of working with primary sources, I present this two-part learning activity designed to introduce students to the different types of primary documents cited by International Relations researchers and teach them the principles of source triangulation. This will equip them with the practical epistemological skills to navigate the complexities of IR research with greater confidence and precision.

Part I: Evaluation

Overview

This activity begins with an in-class group discussion in which students collectively interrogate all twelve types of primary sources. Following this introductory session, students independently conduct deeper case study research into one selected source type, applying insights from the group discussion to explore its uses, limitations, and applications in a specific context.

Learning objectives

- Develop a foundational understanding of the strengths, limitations, and best applications of all primary source types in IR research.

- Practise group discussion and collaborative analysis to synthesise diverse perspectives.

- Conduct independent research to apply and extend understanding of a specific source type in a real-world context.

Instructions

In-class group discussion (small groups)

Step 1: Group formation

Divide students into groups of 3–4. Each group will collectively examine all twelve types of primary sources.

Step 2: Guided source interrogation

Provide each group with a handout summarising the types of sources (based on the provided analysis) and a set of guiding questions:

- What are the main strengths and limitations of this source type?

- In what circumstances would this source be most useful?

- What challenges might a researcher face when working with this source?

- How does this source complement or contrast with others?

Groups work collaboratively to address these questions for all twelve source types. Encourage groups to draw on examples from their own knowledge or previous coursework.

Step 3: Class debrief

Bring the class together to share key points from their group discussions. Facilitate a plenary discussion that highlights patterns, contrasts, and insights, linking the source types to broader IR research themes (e.g., bias, accessibility, and triangulation).

Individual case study research (independent work)

Following the group discussion, each student selects one primary source type to research in greater depth.

Step 1: Selecting a source type

Students choose a source type that interests them or aligns with their research interests.

Step 2: Case study investigation

Each student investigates a specific example of their chosen source type (e.g., a government document, an NGO report, or media coverage of a crisis). They prepare a case study addressing the following:

- Context: Describe the source and its relevance to a specific IR issue.

- Analysis: Evaluate its strengths, limitations, and optimal applications.

- Reflection: Discuss how this source type complements others and its role in broader IR research.

Step 3: Submission and feedback

Students submit their case studies for assessment and receive feedback.

Assessment and reflection

Group work assessment: Participation in the group discussion is informally assessed based on engagement and contribution.

Individual case study assessment: Case studies are evaluated for depth of analysis, clarity, and critical engagement with the strengths and limitations of the chosen source.

Reflection: Encourage students to reflect on how the initial group discussion informed their individual research.

Outcome

By engaging in collaborative discussion before independent research, students develop a broad understanding of all primary sources in IR, which they then apply to a focused analysis. This dual approach fosters both collective learning and individual critical thinking, equipping students with the skills to evaluate and utilise diverse primary sources effectively.

Part II: Triangulation

This follow-up activity introduces students to the practice of source triangulation by comparing diverse primary sources in small groups to identify patterns, contradictions, and biases. Students then apply these skills individually to a chosen case study, integrating insights from multiple sources into a cohesive analysis.

Learning objectives

- To understand the concept of source triangulation and its importance in International Relations (IR) research.

- To develop skills in critically comparing and integrating information from multiple primary sources.

- To practice applying source triangulation to build a coherent and evidence-based analysis.

Instructions

Step 1: Pre-class preparation (individual)

Prior to the in-class activity, student should prepare with the following:

- Students will review a short primer or reading on source triangulation (provided by the instructor).

- Each student selects a recent international event or issue (e.g., a diplomatic crisis, humanitarian intervention, or climate summit) as their case study.

- Students gather one primary source relevant to their chosen event, such as a government statement, NGO report, or media article.

Step 2: In-class group discussion (small groups of 3–4)

Sharing individual sources (15 minutes)

Each student briefly presents their primary source, highlighting:

- The source’s key information.

- Its strengths and limitations as a standalone source.

- How it might contribute to understanding the selected event.

Group comparison and cross-checking (20 minutes)

As a group, students examine how their sources compare and contrast:

- Are there areas of agreement or corroboration between the sources?

- Are there contradictions, and what might explain them?

- Do any biases or gaps in one source get addressed by another?

Groups categorise the sources (e.g., official, media, NGO) and discuss how different types contribute to a fuller understanding of the issue.

Developing a triangulated insight (10–15 minutes)

Groups work together to synthesise their findings, writing a short summary of:

- Key insights from the triangulation process.

- Questions that remain unresolved or require further investigation.

- A preliminary conclusion about the event based on the combined sources.

Step 3: Post-class individual research and analysis

Task: Applying source triangulation

Students expand their case study by collecting two additional primary sources that provide diverse perspectives (e.g., one NGO report and one media article to complement a government document).

Using these three sources, students write a short analysis (500–750 words) that includes:

- A brief overview of the event or issue.

- A critical evaluation of each source’s contribution, strengths, and limitations.

- An explanation of how source triangulation enhanced their understanding of the event.

- A final evidence-based conclusion that integrates insights from all three sources.

Assessment and feedback

Group discussion summary:

- Students submit their group’s triangulation summary for feedback.

- The instructor evaluates how effectively the group identified patterns, discrepancies, and biases.

Individual analysis:

The written analysis is assessed for:

- Depth of source evaluation.

- Effective integration of evidence.

- Coherence and persuasiveness of the conclusion.

Class reflection (optional):

- In a follow-up session, students share their experiences with triangulation, discussing challenges and insights gained.

Summary

Effective research in International Relations demands more than surface-level engagement with evidence, it requires a critical and reflective approach to primary sources. By evaluating the strengths, limitations, and best uses of these materials, students gain a foundational skill set that supports rigorous and insightful analysis. Collaborative discussions and case study research further reinforce these competencies, fostering both teamwork and independent inquiry.

The follow-up focus on source triangulation builds on this foundation, emphasising the value of integrating diverse sources to develop a more comprehensive understanding of global events. This process not only enhances analytical rigour but also encourages students to approach research with an inquisitive mindset. As they master these techniques, students will be better prepared to navigate the challenges of IR research.

Suggested resources

These sources provide a foundation for understanding the methodological challenges and techniques, including source evaluation and triangulation, in International Relations research.

(2024). Research Methods in International Relations. E-International Relations.

Habib, B. (2015). Balance of Incentives: Why North Korea Interacts with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Pacific Affairs. 88(1), 75-97.

Hales, D. (2010). An introduction to triangulation. UNAIDS.

Kern, F. G. (2018). The Trials and Tribulations of Applied Triangulation: Weighing Different Data Sources. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(2), 166-181.

Lamont, C. (2021). Research Methods in International Relations (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Obar, J. (2021). Source Triangulation Skills and the Future of Digital Inclusion: How Information Literacy Policy Can Address Misinformation and Disinformation Challenges. Yale Law School.

Pierce, R. (2008). Evaluating information: validity, reliability, accuracy, triangulation. In Research Methods in Politics. SAGE, pp. 79-99.

Roselle, L., Shelton, J.T., & Spray, S. (2019). Research and Writing in International Relations (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Tan, E.-W. (2019). Source Triangulation as an Instrument of Research on North Korea. North Korean Review, 15(1), 34–50.

Trachtenberg, M. (2006). The craft of international history: A guide to method. Princeton University Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.