From 2015-2021 I worked on a participatory-action research project exploring the politics of the global permaculture movement. I interviewed over 60 permaculture practitioners from around the world. This 10-part series summarises the findings from those interviews and caps my contribution to the permaculture movement.

The purple section of RetroSuburbia by David Holmgren (2018)—’The Behavioural Field: Patterns of Decisions and Actions’ (chapters 24-34)—is less about actual socio-economic patterns in community and more a collection of homespun thought bubbles. I don’t know why this section was included, as it devalues the excellent technical design strategies across the rest of what is otherwise and excellent book.

The RetroSuburia example highlights a tension in permaculture thinking between its robust critique of capitalism and its explicit commitment to quaint models of village-level rural-agrarian socio-economic organisation. Is the permaculture movement brining a knife to a gunfight in its critique of capitalism?

Mollison and Holmgren’s writings emphasise that industrial capitalism, with its relentless pursuit of profit, has led to widespread environmental degradation and social inequities. They argue for a radical transformation of our economic systems to prioritise ecological balance and community well-being over consumerism and growth. This critique resonates with many who feel disillusioned by the failures of capitalism to address urgent environmental concerns.

Yet bolshie rhetoric aside, an important question arises: what would a radical overhaul of the capitalist political-economic systems actually entail, and are permaculture-inspired economic regeneration strategies up to the task as vehicles for that transformation?

I argue that they are not on their own, but they could be a useful compliment to a broader political-economic project to transform the economic system across local, national and global scales. However, to borrow from Lord of the Rings, this will require a little less Hobbiton and a little more Middle Earth in how permaculture thinking grapples with economic regeneration.

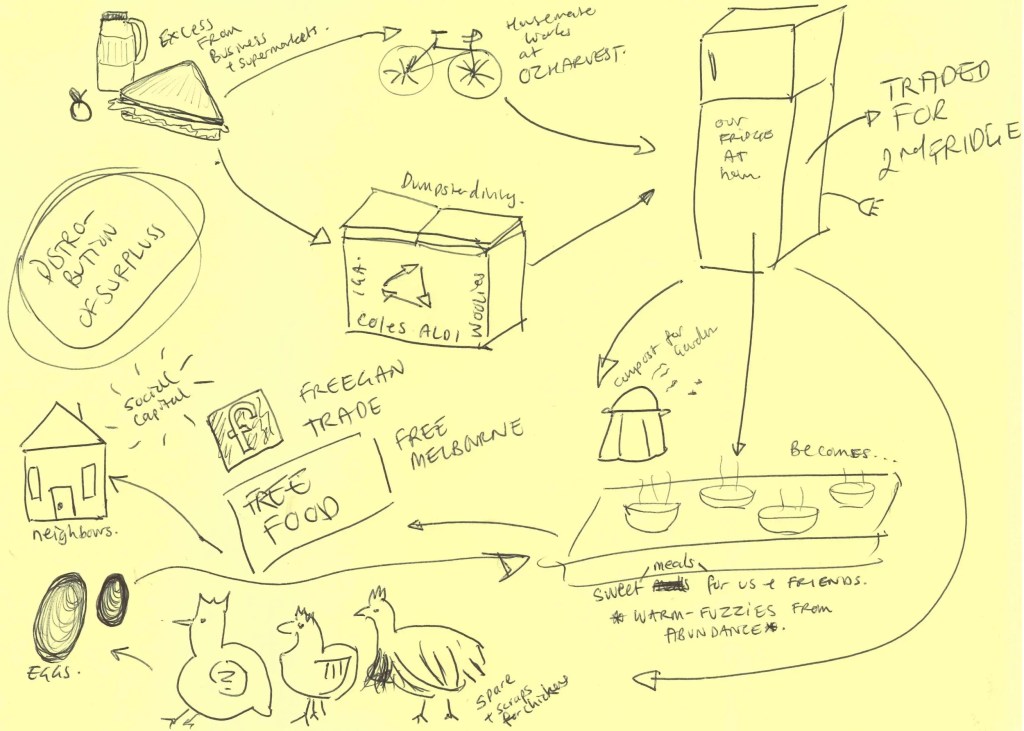

Drawings created by CERES PDC students in my session on economic regeneration strategies, who were asked to visualise their connection to the economy (Habib 2018).

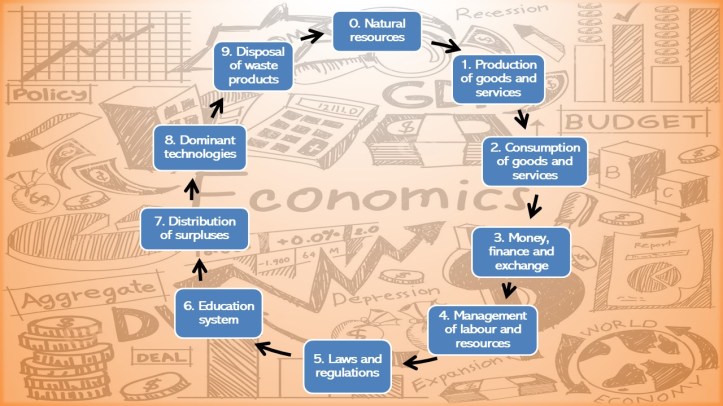

Structural features of the capitalist political-economic system

The list below is a heuristic framework documenting a series of ten different but inter-related structural features of political-economic systems. All political-economic systems have these structural features in one way or another, illuminating the interconnections between governance, ideology, and economic activity, revealing the deeply political nature of economic processes. In teaching my units on socio-economic permaculture in the Permaculture Design Course at CERES Community Environment Park in Melbourne, I encouraged participants to identify what each of these structural features look like in the capitalist economic system and identify permaculture-inspired interventions that might further Earth Care, People Care and Fair Share in the context of each element.

Permaculture interventions offer a spectrum of potential outcomes ranging from adaptive palliatives to systemic transformations, depending on their scale, integration into existing systems, and ability to challenge capitalist paradigms. While permaculture inherently critiques the extractivist, growth-driven nature of capitalism, its practices often operate within the constraints of capitalist economies, raising questions about their transformative capacity.

The 10 structural elements of the capitalist political-economic system manifest differently across global, national, and local scales, reflecting distinct dynamics and interdependencies shaped by flows of power, resources, and influence.

Natural resources

These constitute the material basis for all economic activity, the foundational materials and assets provided by the environment, such as minerals, water, and forests, which are harnessed for economic development and societal needs.

In capitalist systems, resource ownership is often conceptualised through frameworks of private property and state-sanctioned commodification, enabling natural assets to be treated as economic goods subject to market forces (Polanyi 1944). This approach often prioritises extraction and profit over stewardship and equity, resulting in over-exploitation and environmental degradation (Martinez-Alier 2002). Nature is rarely managed as a commons, with only limited exceptions such as communal water systems or indigenous land management practices (Berkes 2008).

Natural resources extracted in the Global South are overwhelmingly used to fuel the economies of the Global North, with multinational corporations often controlling extraction and profits accruing to shareholders in wealthy countries (Martinez-Alier 2002). Nationally, states mediate resource use through concessions to corporations or state-owned enterprises, tying revenues to development goals or debt repayment (Bridge 2008). At the local level, communities near extraction sites face displacement, pollution, and social disruption, often with limited capacity to resist or influence global markets (Escobar 2012).

By contrast, permaculture design thinking views natural resources as commons, advocating for practices that integrate ecological regeneration with equitable access. For instance, community land trusts and regenerative farming practices, such as silvo-pasture and agroforestry, align with principles of Earth Care and People Care by enhancing biodiversity and ensuring that communities share the benefits of natural resources (Ferguson & Lovell 2014; Mollison 1988).

“I see the re-localisation of resources (food, energy, education etc) and the reconnection with community and culture as an appropriate goal for the permaculture movement both within my local area and more broadly on a global scale. Ideally, people should be consuming more within the limits of their surroundings and harvesting food and energy from local and natural sources. This would hugely reduce the strain on the environment in terms of minimising fossil fuel extraction and deforestation” (Interviewee #34).

Permaculture’s approach to natural resources as commons rather than commodities holds transformative potential. By challenging the capitalist logic of private ownership, interventions like community land trusts and ecosystem restoration projects embody a systemic critique of resource commodification (Bollier & Helfrich 2012).

However, their limited scale and reliance on external funding often tether them to capitalist structures, making them more adaptive than transformative in practice (Ostrom 1990). For example, while permaculture principles promote ecological regeneration, their implementation often occurs within market-driven contexts, such as certified organic farming, which commodifies ecological values.

Production of goods and services

The processes and mechanisms through which societies create value by transforming resources into usable outputs, including industrial, agricultural, and service-based activities.

The production of goods and services in capitalist systems is predominantly controlled by private corporations, whose motivations are driven by profit maximisation rather than sustainability or public welfare (Schnaiberg 1980). This focus often results in large-scale industrialisation and the externalisation of social and environmental costs (Foster et al 2010).

“Oh, I’d say number one would be the [world arms] industry, right across the world. I think that when I look at the resources that that’s syphoning out of the countries – we’re looking at 15 million for a plane that can fall out of the sky. We’re looking at billions for submarines that just come out of the water” (Interviewee #1).

At the global level, production is dominated by transnational corporations leveraging supply chains to exploit disparities in labour costs and environmental regulations (Harvey 2014). National governments compete to attract foreign direct investment by offering tax incentives and deregulation, positioning their economies within the global division of labour (Rodrik 2012). Locally, production ranges from small-scale enterprises to factory operations, with industrial communities particularly vulnerable to economic shocks such as automation or factory closures (Standing 2021).

“How do we actually evaluate that? I don’t know. Because of our position, we just – quite recently, we got approached by a large shopping centre. They want to – so this is big central, in a major capital city – they wanted to do a redevelopment of that shopping space and they wanted to put in a function centre, and a small urban farm, and they wanted to do it all with 100 percent highest level environmental and permaculture ethics. And I have no doubt that there were people in that project whose intent is pure. But they’re doing it as part of development with a 20-storey apartment building as part of that and we just looked at it – reading through it and it was actually comical. We were laughing. A group of us was reading this proposal and we were just laughing at how comical it was that somebody could think that a massive shopping centre in the middle of a major capital city with a 20-storey apartment building could be permaculture. There is such a huge disconnect between what – the way that I believe every large business generates its income and hence – and that the environmental destruction and social destruction that all of those enterprises rely on and hence government activity at that scale is fundamentally tarnished by that behaviour that even engaging with almost anything at this larger scale, even universities and hospitals and structures like that is so compromised” (Interviewee #16).

Capitalist production systems prioritise profit and efficiency, often externalising ecological and social costs (Bunker 1988; Harvey 2014). Permaculture-inspired interventions challenge this extractivist approach by promoting decentralised, community-led production systems that prioritise resilience and sustainability. Bioregional economies, which advocate production within ecological limits, reduce dependency on globalised supply chains while lowering carbon footprints (Trainer 2010). Regenerative systems such as permaculture food forests and closed-loop industrial processes exemplify how production can restore ecosystems while meeting human needs, ensuring distributive justice and ecological regeneration (Holmgren 2017).

“I do see for example, the British Permaculture Association, who have built really good links with ethical enterprises like Lush Cosmetics who are funding them. So Lush wants to be greener than green and whiter than white when it comes to its environment for sustainability record and not only do they go to extreme lengths to source almonds that haven’t just been certified organic but they definitely don’t have other impacts on the environment. So they go above and beyond quite high standards but then they also put money into their stuff and they put money into things like permaculture as part of their social responsibility” (Interviewee #13).

However, such systems frequently operate on the margins, dependent on niche markets and voluntary participation. They can be seen as adaptive responses to capitalism’s ecological and social failures rather than direct challenges to its systemic drivers (Trainer 2010). Transformative potential exists if such models are scaled and integrated into broader economic reforms that dismantle extractivist production structures, but this requires political and cultural shifts beyond permaculture alone (Schumacher 1973).

Consumption of goods and services

The patterns and practices by which individuals and groups utilise products and services to satisfy needs, desires, and sustain livelihoods.

Consumption in capitalist economies is shaped by income inequality, cultural norms, and the marketing of aspirational lifestyles, resulting in overconsumption by affluent groups and unmet needs for marginalised populations (Bourdieu 2013). Patterns of consumption are heavily influenced by advertising and the creation of consumer desire, often promoting short product lifecycles and disposable goods (Baudrillard 1998). The benefits of consumption are therefore unevenly distributed, with the wealthiest segments of society disproportionately able to satisfy desires, while others struggle to meet basic needs (Galbraith 1958).

“So, impediments to it spreading – again, I think a lot of it is just the – it’s just drowned out by all the craziness of the world. It’s drowned out by things like mortgages. People wanna own a home. They are just so hunkered down. I mean capitalism generally is just a complete fuck up. So people are just working so hard just to keep a roof over their head, keep food on the table, try and keep the kids going to school and not taking ice” (Interviewee #48).

Consumption patterns are heavily shaped by global advertising and consumer culture, which drive homogenisation and resource-intensive lifestyles in wealthier nations (Baudrillard 1998). Nationally, governments often prioritise consumer spending to drive economic growth, subsidising industries such as housing and automobiles to encourage consumption (Galbraith 1958). However, at the local level, consumption is marked by inequality, with wealthier communities accessing diverse goods while poorer areas face limited options or rely on informal markets (Jackson 2009).

“But then the second one is poor self-image and – or lack of self-love, let’s call it that, lack of self-love. So, these are the types of things that drives people to consumption because they’re trying to fill this hole. They wanna love themselves. They don’t feel comfortable in their own skin type thing. And so, lack of self-love. It also causes people to be angry and conflict because hurt people hurt people, so find out where love – people would feel love and are loved” (Interviewee #14).

Consumption in capitalist systems is heavily shaped by consumerism and planned obsolescence, resulting in overconsumption and inequality (Jackson 2009). Permaculture-inspired approaches encourage mindful consumption through practices such as tool libraries, community-supported agriculture (CSA), and repair cafés, which foster sharing, reuse, and minimal waste (Seyfang 2009). These strategies align with the permaculture principle of Fair Share by redistributing resources and promoting sufficiency, addressing ecological and social inequities while reducing the ecological footprint of consumption (Holmgren 2017).

“And putting our money where we want to vote for supporting that salsa that’s organic and local as opposed to the mass produced one, even though it’s a dollar more or two, or understanding more about the local economy and how if we’re putting our money into local economy, then more like 97% of that is going to stay rather than taking it to a stupid market, where we’re stupid enough to keep going back there and pouring our money into the 97% that’s just going to be exported immediately” (Interviewee #18).

“If they’re more interested in changing the planet from the point of view of consumption and the overreliance on fossil fuel-based production, then this is a great way to do it because every decision you make is governed by the principles and it becomes second nature. So every time you do anything, you may still decide not to forego your overseas holiday but you will have thought through all the implications of what your decisions mean” (Interviewee #48).

While these initiatives promote values counter to consumerism, they typically rely on voluntary participation and appeal to niche demographics, limiting their systemic reach. Their transformative capacity depends on embedding these practices within broader economic systems, such as policies incentivising circular economies or reducing planned obsolescence (Jackson 2009).

Money, finance, and exchange

The systems of currency, credit, trade, and investment that enable economic interactions, facilitate transactions, and mobilise resources across different sectors.

Capitalist financial systems facilitate economic interactions but also perpetuate inequality and instability. Financial markets are geared towards capital accumulation, privileging wealth holders while marginalising those with limited access to credit or capital (Keynes 1936). Speculative investment, particularly in derivatives and other financial instruments, can exacerbate economic volatility, as evidenced by the 2008 financial crisis (Stiglitz 2010). At the same time, globalised finance creates barriers for local economic development by redirecting wealth into transnational flows rather than local reinvestment (Rodrik 2012).

“So, I’ve been considering about – at the moment, I’m in a credit union, but then I’m looking at examples like the Barefoot Investor and doing very minimum bank accounts. And then there’s online since like we’re online, too. I don’t know who these bank accounts are. I know my local credit union. I can speak to the people, they know me, and I know it’s a co-op as well. So we’re all members, and which for sure are not going to be going down the coal seam gas path with it. And I can ask them very specifically, who are you investing in and then who you’re not from the beginning. But then there’s other places where you can, for sure, put your money into very low interest, or no interest accounts, but where are they investing their money? And it’s often those larger banks and larger cartels which are really taking away from family businesses and the corner shop or the local hardware of the nurseries and we’re taking away the diversity and therefore nutrition and therefore soil ecology and therefore the microbes’ life” (Interviewee #18).

Money, finance, and exchange operate as interconnected systems across scales. Globally, financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank influence currency values, investment flows, and debt policies, while speculative markets exacerbate volatility (Stiglitz 2010). National governments manage monetary systems through central banks, regulating interest rates and stabilising economies during crises, such as the 2008 financial meltdown (Mishkin 2010). Locally, financial systems include credit unions and microfinance institutions that support small businesses and individuals but remain vulnerable to external shocks (North 2010).

Capitalist financial systems concentrate wealth and exacerbate inequality, often prioritising speculative gains over community welfare (Piketty 2017). Permaculture-inspired models of exchange, such as local currencies, time banking, and cooperative lending, decentralise economic control and foster resilience (North 2010). Ethical investment in regenerative projects, such as renewable energy cooperatives or community reforestation schemes, redirects financial flows toward ecological restoration and social equity, embodying the principles of Earth Care and People Care (Hildyard 2016).

“I want to bring credit into permaculture in developing countries because the local land [owner] and the local banks are paying 60 percent a year – is immoral and [unconscionable]. So, I’m not sure that they’d even do that. I think that what they do is probably very well in their patch, but as we know, it’s just a tiny section of perma – it’s a little bit of [zone three], it’s not even all of it. So, you could take that” (Interviewee #1).

While these models disrupt capitalist concentration of wealth in specific contexts, they often coexist with mainstream financial systems, limiting their transformative impact (Douthwaite 1996).

“Resources. I don’t know ‘cause everybody is all doing totally different things. Everybody is totally doing different things. And I love the fact that actually people in the global permaculture movement who are business people themselves, they’re with consultancy, they have successful projects that are making money. So I don’t know resources. I don’t know. I actually feel that we have some of the resources that we all need within the network but we’re not connecting well and we’re not utilising whatever it is that we have” (Interviewee #6).

“You know we all have to live, so what’s happening is that it’s coming back, “Is it financially sustainable? How does a permaculturist make money ethically and morally?” So o then the question comes, if you started giving everything free or – so somewhere, there has to be a little bit more support maybe on resources where the permaculture people don’t have to be become commercially minded. So let’s just say we’re doing a PDC or any workshop, we call in 15 people from outside, and if ten is breakeven and you wanna actually push for 15 and somebody else helped with that five and this guy doesn’t have to do all the commercial stuff. Somewhere, you need that support, I think. That’s not happening – so the fair share is not between just you and me. You’re coming for the course and I’m giving you the course. It’s not the transaction with me. Somewhere you guys, as the community, need to help this partnership. So fair share today is becoming – it’s been two people. It’s not. I think somewhere your ten dollars, her ten dollars, his ten dollars, that can actually help this transaction to happen as well. Perhaps we need to think of collective fair share and not put that on the individual and say, “Oh, you’re the permaculturist, it’s your responsibility, go figure that out”” (Interviewee #9b).

To achieve systemic change, these interventions would need to be embedded in broader financial reforms, such as wealth redistribution mechanisms or the abolition of speculative markets (Douai 2017).

Management of labour and resources

The policies and institutions governing the allocation, organisation, and utilisation of human and material resources within a society.

Labour and resource management in capitalist systems is characterised by hierarchical control, often with minimal worker participation in decision-making processes (Braverman 1974). Power dynamics heavily favour employers and resource owners, with workers frequently subject to exploitation through wage suppression, precarious contracts, and unsafe conditions (Standing 2021). Resource allocation tends to prioritise profitability over equity, often ignoring the social or ecological costs of such decisions (Giddens 1990).

“So I write pandemic plans, heat wave plans, emergency animal welfare, so what if – I’ve gotta be thinking about, “Okay, so what if the foot and mouth breaks out here?” What happens with the stand still? Where does that go? What happens to all the farmers in our local area where we live? We’re gonna have mental health issues if they know that – because 60 percent of our meat goes overseas – if they know that they probably don’t have an income for the next two years. I work with snow, I work with fire, I work with floods, and the fact that insurance companies – and they are not gonna be – they’re looking for ways to not insure you for those things so – and that comes into working with not only heat waves, but what happens when power is out? They’re gonna do power load shifting. So what happens to those people in vulnerable communities or vulnerable people? Anyone can be vulnerable at any time when the power is out on a 40-degree day three days in a row or in the middle of winter. So permaculture has answers to all of those things but <laugh> – and that’s where it gets a bit exciting. It’s like, wow! We can! This permaculture can actually be seen as something that’s reputable. We can actually make some big changes” (Interviewee #45).

Labour and resource management similarly vary across scales. Globally, supply chains exploit wage and labour law disparities, while migrant labour flows sustain industries in wealthier countries (Sassen 2013). Nationally, labour policies, such as minimum wage laws or worker protections, reflect political priorities and economic competition (Standing 2021). Locally, labour markets are shaped by informal economies and community-based resource management practices, such as cooperatives or collective forestry, which reflect attempts to balance equity and sustainability (Ostrom 1990).

The capitalist organisation of labour and resources frequently marginalises workers and disregards ecological boundaries, prioritising profit maximisation (Moore 2015). Permaculture design promotes equitable and participatory resource management through worker-owned cooperatives, permaculture guilds, and community resource-sharing initiatives (Ferguson & Lovell 2014). Practices such as rotational grazing and permaculture-based forestry align labour with ecological cycles, enhancing productivity while regenerating ecosystems (Holmgren 2017).

“In terms of business, we’ll see. I’m really excited about the social permaculture work that’s happening – trying to help business and organisational structures to take that step into next paradigm of business and enterprise. I think that’s super exciting to see these organisational models like sociocracy and holacracy and other things that mimic the patterns found in nature with the beehives and everything. So, that’s exciting to see. And also, businesses like social enterprises that are embracing the triple bottom line – people, planet, and profit – and with permaculture, we have people, planet, and fair share. So, I think there’s some healthy overlap” (Interviewee #25).

These models redistribute power and prioritise equity, challenging capitalist dynamics of labour exploitation. However, their transformative potential is limited when operating within a broader capitalist framework that prioritises profit and competition.

“Look, I think it’s problematic. I think people who get into permaculture as a rule are maybe not engaging with those guys, mostly just doing their own thing. I see myself as – and I think most permaculture teachers are like this. We occupy this odd space because what we do is really, really focused on community, on building community, on upskilling the community, but we’re not not-for-profits. So, we don’t get a lot of perks that not-for-profits get. So I come up against that a lot. For example, I’m doing a World Food Day stall on the weekend here, but I’ve had to go off and buy expensive insurance because the Latrobe City Council won’t – I don’t come under their insurance because I’m a business and not a not-for-profit. If I was not-for-profit, I could get free insurance, things like that. So, it’s a bit of a – in a weird way, it kind of straddles kind of not-for-profit and business world, but I don’t think I’ve actually heard anybody else talking about that. I should talk about it. Maybe other people will talk to me about it if I talk about it” (Interviewee #48).

“Yeah. That really struck me in that last class that we had <inaudible>, it’s so true. We always knew our business was like that and it’s becoming more and more like that because the more we need money to survive, the less we’re taking on the jobs where we’re not being united in a way in which it sustains us. So it’s actually making us more specialised and making our client-based more specialised” (Interviewee #26).

For systemic change, such models must be coupled with policies promoting collective ownership and resource sovereignty at scale (Gibson-Graham 2006), otherwise the capacity for practitioners to make a living through permaculture practice is limited.

Laws and regulations

The legal frameworks and policies established to oversee economic activities, enforce standards, and resolve conflicts, which define the boundaries of market and non-market interactions.

Laws and regulations in capitalist systems are shaped by the interests of powerful economic actors, with states often enforcing property rights, intellectual property protections, and labour laws that favour corporations (Offe 1984). While environmental and social regulations exist, their implementation is frequently weak or inconsistent, driven more by political expediency than long-term sustainability goals (Dryzek 2022). Regulatory frameworks can also be undermined by lobbying and political donations, creating a system of governance that privileges capital over public welfare (Streeck 2016).

“Lot’s of practical solution used in permaculture are not allowed in the national legal context or there are no legal rules for them (e.g: home education, eco-building, forest gardening etc.) as people in the movement try to find solutions for these often in confrontation with legal authorities, therefore the movement has a political force in itself” (interviewee #29).

Laws and regulations governing capitalist systems also differ by scale. Global frameworks, such as those under the WTO or Paris Agreement, set trade and environmental standards but often favour powerful nations and corporations (Streeck 2016). Nationally, legal systems regulate industries, enforce property rights, and manage market interactions, frequently influenced by lobbying and global pressures (Harvey 2005). Locally, governments adapt and enforce regulations through zoning laws or community by-laws that reflect local priorities and needs (Dryzek 2022).

Capitalist legal frameworks often prioritise corporate interests, undermining ecological and social well-being (Harvey 2005). Permaculture-informed interventions advocate for policy reforms that embed ecological stewardship into governance, such as legal recognition of the rights of nature or land-use policies promoting regenerative agriculture (Shiva 2005). By integrating Earth Care and People Care into regulatory frameworks, these approaches challenge the dominance of extractivist and profit-driven legal systems (Ostrom 1990).

“I am a core member of a local environmental NGO in the village where I live, acting in diverse ways of creating sustainable solutions. (e.g: conserving local, traditional fruit varieties, organising local programmes for increasing local consciousness, achieving local legal protection for trees etc.)” (Interviewee #29).

“Some exceptional individuals, many doing this, are not publishing their work to the Permaculture movement. But on the whole, if you don’t present as a professional and have other professional qualifications and affiliations, Permaculture as it presents won’t get you in the door. For instance very few in Permaculture know of my work in four levels of Australian governments, or lecturing at the two big universities at Canberra (UC & ANU) for 13 years, or being a project manager on the Goulburn Wetlands Restoration Project as 1 of the 3 project managers. They would also probably not regard my work on Australian Water Quality Policy, environmental law enforcement on catchment protection of Sydney’s water, or forming Landcare Groups, as their version of Permaculture. Those practitioners engaging with governments successfully, do so, as somewhere in the professional ranks is a covert Permaculture operative!” (Interviewee #37).

While these reforms hold transformative potential, they are often diluted by capitalist pressures, resulting in incremental adaptations rather than systemic change. For instance, greenwashing practices often co-opt the language of permaculture without addressing underlying exploitative structures (Dryzek 2022).

Education systems

The structures and institutions responsible for imparting knowledge, skills, and cultural values, shaping the workforce and influencing long-term economic and social development.

In capitalist systems, education often serves the dual purpose of reproducing social hierarchies and preparing a workforce suited to market demands (Bowles & Gintis 1976). Access to quality education is often uneven, reflecting broader patterns of inequality, with wealthier groups benefiting from better facilities and resources (Bourdieu & Passeron 1990). Educational priorities, as articulated at the managerial levels of education systems, neglect ecological literacy and critical thinking, focusing instead on vocational skills that reinforce existing economic structures (Sterling 2001).

Education systems, while globally influenced by organisations like UNESCO, focus on universal access and workforce preparation (Spring 2014). Nationally, education policies shape curricula to align with economic priorities, often reinforcing political ideologies (Bowles & Gintis 1976). At the local level, disparities in funding and access are evident, with community-driven initiatives such as permaculture schools addressing gaps left by formal systems (Sterling 2001).

Permaculture-inspired education promotes systems thinking and practical skills, with initiatives such as forest schools, permaculture design courses, and community workshops fostering ecological resilience and social equity (Holmgren 2017). These approaches cultivate the knowledge and values needed to challenge unsustainable socio-economic systems, aligning education with permaculture ethics.

“And I feel like it’s important that some of these basic systems are more widely educated about – and whether that’s like just starting from, from the ground up from when children are educated, homes and garden. Having these home garden systems is really beautiful with schools. It’s critical to see where food’s coming from and even the smallest scale garden or balcony can still contribute towards bringing that life back in and that seed-saving community gardens those are older, the plot systems from Europe that brought in allotments. It’s in those higher living urban density areas still being able to still have those farming practices and for children to see families getting together and harvesting food” (Interviewee #18).

“Yeah. And then you hear the odd stuff like I know was able to get something in the state. One of the speakers of the conference has gotten vermicomposting into tenth-grade books and stuff in our schools. And I know that there is now UK universities that have permaculture and university in Australia where you can do permaculture. So, I think if it’s getting into some of those mainstream systems of education, etcetera, then hopefully it will. It’s getting that recognition at that level. Then it should be able to penetrate through governments as well and stuff – it’s got long ways to go” (Interviewee #10).

Permaculture-inspired education fosters ecological literacy and systems thinking, countering the instrumentalist orientation of capitalist education systems (Sterling 2001). However, such initiatives are often underfunded and peripheral, limiting their impact on mainstream education.

“Three years ago we tried to start up a trust fund, an environmental trust fund, for the corporate world, so we’re calling it in our language in <inaudible>, that’s a future fund. It’s like a future fund. So it was an environmental trust fund where companies had to fund schools for example, because all our funding we get is from writing proposals and all that. So we’re hoping to get like more local funding from companies and banks and whatever. So we tried to set up this <inaudible> fund and invited people for the meetings and no one tried to set it up. It was a total failure. No one even contributed a single cent. So it was a big challenge. I’m trying to revive it again, and also trying to look at – because I work with schools, I’m trying to look at alumni. Like for example I target, “Oh, this school has this successful person who use to be here,” and they might even have an attachment to the school. So I’m trying to identify those and then knock on their doors and see whether their companies or they and individuals may be able to assist some of the schools that we’re working with” (Interviewee #6).

Their transformative potential lies in embedding these principles within public education systems, requiring political support and a cultural shift towards valuing ecological knowledge over market-driven skills (Orr 1994).

Distribution of surpluses

The methods and systems by which excess economic output is allocated, whether through private accumulation, public redistribution, or other mechanisms, determining societal equity and access.

Surpluses in capitalist systems are generated through private profit accumulation, with minimal redistribution to address inequalities (Roemer 1994). Taxation and welfare mechanisms are often insufficient to counteract the structural inequalities embedded in profit-driven economies (Atkinson 2015). Those who control capital disproportionately benefit from surplus distribution, while workers and marginalised groups are left with limited access to the resources required for social and economic mobility (Harvey 2012).

The distribution of surpluses is marked by significant inequality. Globally, wealth is concentrated in multinational corporations and wealthy nations through trade imbalances and profit repatriation (Piketty 2017). Nationally, tax policies and welfare systems attempt redistribution, though neoliberal austerity often limits their effectiveness (Harvey 2014). Locally, cooperatives and mutual aid networks provide community-based mechanisms for addressing inequities, reflecting grassroots approaches to redistribution (Seyfang 2009).

Permaculture-inspired interventions advocate for equitable surplus distribution through cooperative models, community food-sharing programmes, and gleaning networks, ensuring resources are redistributed to meet communal needs (Seyfang 2009). These practices advance Fair Share by challenging extractivist norms and fostering community resilience (Holmgren 2017).

“We live primarily within our ecology, but then we live within our society and the economy that – the constraints of that economy as they are placed on us. We have to – and unless you completely fly under the radar, you’ve got to pay rates if you have land. You’ve got to pay taxes every time you buy something. You’ve got GST whether you earn a certain amount or not. And that whole issue of how much we participate in society and how much we fly under the radar is one thing where I actually take a little bit of umbrage with mainstream permaculture, because I think there’s a little bit too much of the individualist” (Interviewee #22).

While these practices challenge capitalist accumulation, their dependence on voluntary participation and limited scale often makes them adaptive responses to inequality rather than systemic alternatives. Structural change requires integrating such practices into broader economic reforms, such as universal basic income or progressive taxation systems (Raworth 2017).

Dominant technologies

The prevailing tools, systems, and innovations that drive productivity, influence economic structures, and alter societal interactions.

Technological development under capitalism is driven by market forces, prioritising innovations that enhance profitability rather than addressing societal or ecological needs (Marcuse 1964). Technologies such as automation and artificial intelligence often increase productivity but exacerbate labour displacement and deepen social inequalities (Brynjolfsson & McAfee 2014). Meanwhile, the environmental impacts of dominant technologies, including resource depletion and waste generation, are frequently overlooked in favour of short-term economic gains (Jasanoff 2004).

Dominant technologies, developed and patented in global hubs like Silicon Valley, reinforce global inequalities through intellectual property laws and uneven access (Jasanoff 2004). Nationally, governments fund technological development through R&D subsidies and public-private partnerships (Mazzucato 2015). Locally, technology adoption depends on access to infrastructure and education, with appropriate technologies tailored to specific community needs, such as sustainable agriculture tools (Schumacher 1973).

“We’ve got all of this metal and all of these machines and all of this stuff and as much as I can look at it and go, well, I don’t think we’re going to be able to do things like that in a sustainable way in the future, they’re still there. And so that can be part of transitional strategies and I suppose I’m interested in that space ‘cause it’s complicated and it essentially involves a lot of compromise where we’re kind of going, well, this might be where we’re heading, but this works now. And how do we do this in a way that actually, my kids, my grandkids, my great grandkids are gonna say “Thanks for doing that” as opposed to, “You bastards.” <laughs>. I always say that about things like international air travel and iPhones and things like that. It’s like, will your grandchildren thank you for any of that? I don’t think they will, because we’re passing on almost nothing of value, leftover from our disposable technology or our excess use of energy. But I like to think that maybe a good olive press, you know, my great grandchildren might go, “Thanks for making that. That’s been really useful”” (Interviewee #22).

Permaculture emphasises appropriate technologies, such as small-scale renewable energy systems, low-impact building methods, and permaculture-based water management systems (e.g., keyline design), which align technological innovation with ecological sustainability and social equity (Holmgren 2017). These interventions empower communities to achieve self-reliance while minimising environmental harm.

“At the moment not very well but improving. PC has marginalized itself by a sustained focus on low tech and not on the mainstream, which is where most people are at present” (Interviewee #38).

“With technology, I mean that’s why I was thinking maybe one of the things is – ‘cause I think permaculture might be – it’s like, “Oh, I don’t want to use a computer” and there’s backlash or resist to it, which is kind of true, I don’t like actually spending too much time using devices and things like that, but I think there is also a lot of tools that are already useful like mapping and GIS, and it think the food movement and the permaculture are becoming a bit more tech-savvy and you kind of have to play the game a bit, so that is the challenge, I think, and some opportunity like it’s a big day to actually do it like that” (Interviewee #21c).

The transformative impact of such technologies is often limited by their marginalisation within broader economic systems. For instance, small-scale renewable energy systems or regenerative water management techniques may displace some reliance on extractive technologies but cannot, in isolation, disrupt systemic reliance on fossil fuels or centralised infrastructure (Jasanoff 2004). How the permaculture movement negotiates the rise of artificial intelligence will also be an interesting watch.

Disposal of wastes

The strategies and systems for managing by-products of production and consumption, addressing environmental impacts and sustainability challenges.

Capitalist waste management practices focus primarily on disposal rather than minimisation or reintegration into production cycles, treating waste as an inevitable by-product of economic activity (Leichenko & O’Brien 2008). Landfills, incineration, and exportation to developing countries are common strategies that externalise the environmental and social costs of waste (Demaria 2010). Although recycling and circular economy initiatives are emerging, they remain marginal compared to the scale of waste generation under prevailing economic models (Geissdoerfer et al 2017).

“I think there’s a ridiculous amount of waste in our system that we wouldn’t condone in our household. So we shouldn’t condone it in our society” (Interviewee #22).

“Our food system, as it stands in the world, is massively dysfunctional. It’s wasteful. It’s polluting. It’s cruel. It contributes massively to climate change. It’s unhealthy. It’s contaminated. There’s so much that’s wrong with it and there’s not a whole lot that’s right with it except that cheap food is available even if it’s not very good food for a lot of people” (Interviewee #48).

Waste disposal illustrates structural inequities across scales. Globally, wealthier nations often export waste to poorer countries, exploiting lax environmental regulations despite international agreements like the Basel Convention (Demaria 2010). Nationally, waste management policies vary in effectiveness, with landfill and incineration dominating in many countries (Leichenko & O’Brien 2008). Locally, municipal systems and informal economies manage waste, with grassroots initiatives such as zero-waste cooperatives demonstrating sustainable alternatives (Geissdoerfer et al 2017).

Capitalist systems often view waste as an externality, neglecting its ecological consequences (Bauman 2013). In contrast, permaculture design incorporates waste into regenerative cycles, exemplified by composting, greywater recycling, and biochar production (Holmgren 2017). Community-scale zero-waste initiatives and repair networks further support sustainable waste practices, ensuring alignment with permaculture principles of Earth Care and Fair Share (Trainer 2010).

“And it’s everything in permaculture about finding unused resources and turning them into things that people who are in your ecosystem can really use. And all my childhood, I’ve been scavenging, turning unused things into useful things” (Interviewee #20).

While these practices reduce ecological harm, their transformative capacity depends on scaling them beyond individual or community initiatives to challenge the structural drivers of waste, such as planned obsolescence and consumerism (Demaria 2010). Policy support for zero-waste initiatives and producer responsibility frameworks could amplify their impact, but such shifts require broader political will and systemic reform.

Advantages of getting systematic

Disaggregating capitalism into its structural elements allows permaculture practitioners to critically examine the complex systems and interdependencies that sustain capitalism. This approach offers several benefits, enhancing their thinking, practice, and ability to address systemic challenges effectively. By breaking down capitalism into its constituent parts, practitioners can move beyond broad critiques to develop targeted, strategic interventions aligned with permaculture principles of Earth Care, People Care, and Fair Share.

Identifying root causes

Analysing the structural elements of the capitalist political-economic system reinforces systems thinking, a core component of permaculture design. By examining how structural elements interact, practitioners can design interventions that address root causes rather than symptoms, fostering long-term resilience (Sterling 2001). Furthermore, this approach encourages ethical reflection on the values underpinning capitalist systems, inspiring practitioners to advocate for economic models that prioritise ecological health and social equity.

“I think that the ethics and principles, if practiced, radically challenge capitalism and its associated systems of oppression (sexism, racism, colonialism, etc.). The ethics alone are completely at odds with a capitalist society. In this way, I think that permaculture is inherently political and should make links with other social movements striving to radically transform our world” (Interviewee #30).

A deep understanding of capitalism’s structural elements enables permaculture practitioners to challenge its underlying paradigms, such as the prioritisation of growth and profit over ecological and social well-being (Jackson 2009). By articulating alternatives and demonstrating viable models of regenerative economics, practitioners can contribute to cultural and paradigm shifts that align with permaculture ethics.

Leverage and scale

Capitalism functions as a dynamic and multi-layered system, with each structural element (e.g., natural resources, labour, laws, money) interconnected and mutually reinforcing (Meadows 1999). Evaluating these elements helps permaculture practitioners understand the specific mechanisms through which capitalism operates, enabling them to identify leverage points where small interventions can yield significant systemic impacts (more about this is Part

“But I step back at the same time because I go, “Well, I’ve got my own battles to fight. I really gotta help this damn world move forward and I can’t afford to be in stuff that’s – and I won’t say wasting my time because it’s not a waste of time, but I have to pick my battles, if that makes sense. I have to pick where I’m gonna be most effective to actually create change” (Interviewee #45).

Exploring the structural features of capitalism in this way counters the tendency to view it as a monolithic or immutable force. Instead, it reveals the diverse ways in which capitalism manifests across scales and contexts, from global supply chains to local consumption patterns (Harvey 2014). This perspective allows practitioners to identify areas where they can exert meaningful influence, avoiding the paralysis that can result from perceiving capitalism as an insurmountable whole (Trainer 2012). This linkage ensures that local efforts align with broader systemic goals, fostering coherence between micro- and macro-level strategies.

Vulnerabilities and opportunities

By analysing capitalism at the level of its structural elements, practitioners can identify vulnerabilities and opportunities for intervention (Altieri 2018). This targeted focus ensures that permaculture strategies address specific issues rather than treating symptoms of broader systemic problems.

“Well, another saying I love is, “We need permacultures on every frontline.” So, we need permaculturalists working in the garden with the soil, but we also need permaculturalists working to help the old system die well, to be hospice workers in that way. We also need permaculturalists who are kind of in positions of power perhaps in the current paradigm and who can really support with resources, with funding, especially these new and emerging projects. So, I suppose our points of leverage are our permie allies in all facets of social structures” (Interviewee #25).

A structural analysis of capitalism equips permaculture practitioners with the knowledge needed to engage effectively with policymakers, businesses, and communities. For example, understanding the role of national laws and regulations in shaping land use can inform advocacy for policies that support regenerative agriculture or the rights of nature (Shiva 2005). Similarly, recognising the influence of dominant technologies on labour markets can guide efforts to promote appropriate technologies that align with permaculture ethics (Schumacher 1973).

Conclusion

While permaculture interventions embody principles that fundamentally challenge the ecological and social injustices of capitalism, their transformative potential is often constrained by their marginalisation within broader economic systems. They frequently act as adaptive responses to capitalism’s excesses, providing ecological and social palliatives without dismantling the systemic drivers of inequality and environmental degradation.

To achieve systemic transformation, permaculture needs to take a systemic political-economy approach that integrates into broader political and economic reforms, addressing structural issues of power, equity, and ecological governance.

Understanding capitalism through its structural elements provides permaculture practitioners with a powerful analytical tool for understanding and addressing the complexities of modern economic systems. Together, these structural elements manifest distinctively at global, national, and local scales, shaped by the flows of power, capital, and influence that characterise the capitalist political-economic system.

This approach allows for targeted, strategic interventions; fosters connections between local practices and global systems; and promotes systems thinking, ethical reflection, and paradigm shifts. By moving beyond broad critiques to engage with the specific mechanisms of capitalism, permaculture practitioners can maximise their impact in creating sustainable, equitable, and resilient systems.

References

Altieri, M. A. (2018). Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture (2nd Ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

Baudrillard, J. (1998). The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. SAGE Publications.

Bauman, Z. (2013). Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts. Polity Press.

Bollier, D., & Helfrich, S. (2012). The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State. Levellers Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2013). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Taylor & Francis.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1990). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. SAGE Publications.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life. Basic Books.

Braverman, H. (1974). Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. Monthly Review Press.

Bridge, G. (2008). Global Production Networks and the Extractive Sector. Journal of Economic Geography. 8(3), 389–419.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W.W. Norton.

Demaria, F. (2010). Shipbreaking at Alang-Sosiya (India): An Ecological Distribution Conflict. Ecological Economics. 70(2), 250–260.

Douai, A. (2017). Ecological Marxism and Ecological Economics: From misunderstanding to meaningful dialogue. In Spash, C. L. (Ed.). Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society. Routledge.

Douthwaite, R. (1996). Short Circuit: Strengthening Local Economies for Security in an Unstable World. Green Books.

Dryzek, J. S. (2022). The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses. Oxford University Press.

Ferguson, R., & Lovell, S. T. (2014). Permaculture for Agroecology: Design Principles for the Ecological Landscape. Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 34(2), 251–274.

Foster, J. B., Clark, B., & York, R. (2010). The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth. Monthly Review Press.

Galbraith, J. K. (1998). The Affluent Society (40th Anniversary Edition). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The Circular Economy – A New Sustainability Paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production. 143, 757–768.

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). A Postcapitalist Politics. University of Minnesota Press.

Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

Harvey, D. (2012). Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. Verso.

Harvey, D. (2014). Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism. Profile Books.

Hildyard, N. (2016). Licensed Larceny: Infrastructure, Financial Extraction, and the Global South. Manchester University Press.

Holmgren, D. (2018). RetroSuburbia: The Downshifter’s Guide to a Resilient Future. Melliodora Publishing.

Holmgren, D. (2017). Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Melliodora Publishing.

Jackson, T. (2009). Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Routledge.

Jasanoff, S. (2004). States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. Routledge.

Leichenko, R., O’Brien, K. (2008). Environmental Change and Globalization: Doubles Exposures. OUP USA.

Marcuse, H. (1964). One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Beacon Press.

Martinez-Alier, J. (2002). The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation. Edward Elgar.

Mazzucato, M. (2015). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. Anthem Press.

Meadows, D. H. (1999). Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. The Sustainability Institute.

Mishkin, F. (2021). The Economics of Money, Banking and Financial Markets (Global Edition). Pearson.

Mollison, B. (1988). Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual. Tagari Publications.

Moore, J. W. (2015). Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. Verso.

North, P. (2010). Local Money: How to Make it Happen in Your Community. Green Books.

Orr, D. W. (1994). Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect. Island Press.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Piketty, T. (2017). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press.

Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Beacon Press.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Rodrik, D. (2012). The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. W.W. Norton.

Roemer, J. E. (1994). A Future for Socialism. Harvard University Press.

Sassen, S. (2013). The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton University Press.

Schnaiberg, A. (1980). The Environment: From Surplus to Scarcity. Oxford University Press.

Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. Harper & Row.

Seyfang, G. (2009). The New Economics of Sustainable Consumption: Seeds of Change. Palgrave Macmillan.

Shiva, V. (2005). Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability and Peace. South End Press.

Spring, J. (2014). Globalization of Education: An Introduction. Routledge.

Standing, G. (2021). The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class: SPECIAL COVID-19 EDITION. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sterling, S. (2001). Sustainable Education: Re-Visioning Learning and Change. Schumacher Society.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2010). Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. W.W. Norton.

Streeck, W. (2016). How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System. Verso.

Trainer, T. (2010). Transition to a Sustainable and Just World. Envirobook.

[…] VII. Engaging with the economy as a system. […]