From 2015-2021 I worked on a participatory-action research project exploring the politics of the global permaculture movement. I interviewed over 60 permaculture practitioners from around the world. This 10-part series summarises the findings from those interviews and caps my contribution to the permaculture movement.

I am concluding this article series at the place where my permaculture journey started: with prophesies about collapse. The backing track is my story of emancipation from the straitjacket of commitment to the energy descent narrative and my relationship with the idea of collapse.

I’m an edge dweller. Political, economic, social and cultural edges are dynamic places to be. They are a laboratory for creativity and re-imagination of the possible (Cooper 2014). The sub-cultures of the edge emerge and exist as necessary escapes from the traumas of mainstream society. Yet not all ideas that percolate from the edge are good ones, and those sub-cultures can’t claim to have changed society unless their lifeways and lessons become re-absorbed by the mainstream as standard practice.

This is the conundrum of the permaculture movement as an edge phenomenon. Permaculture thinking makes claims about being a societally transformative way of living, while many of its practitioners remain terrified of engaging with the broader society it wishes to change. Many permies are content to remain on the edge, and while they do so, their hyperbole about permaculture as “a revolution disguised as gardening” is myopic fantasy. Remaining on the edge is an excuse for permaculture to be impotent. After all, we can’t change the course of Spaceship Earth by clinging self-righteously to the tip of its wing.

The aim of this article is not to dispute that humanity is in a period of systemic crisis, nor do I dispute that societal collapse may be a possibility. Indeed, we are living through a time of polycrisis:

“A global polycrisis occurs when crises in multiple global systems become causally entangled in ways that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects. These interacting crises produce harms greater than the sum of those the crises would produce in isolation, were their host systems not so deeply interconnected” (Lawrence et al 2022).

What I take issue with is the idea in permaculture thinking that collapse is inevitable, and that energy descent is its inevitable pathway, which seems to lead to a lot of adaptation dead ends. This leads to some serious questions: What do permaculture practitioners mean by “collapse” anyway? Are permies always imagining the same thing when they talk about collapse? What assumptions are permies making about the future in their commitment to a specific collapse narrative? Answering these questions requires permaculture practitioners to critically evaluate their collapse narrative and the ideas that underpin it, along with a critical introspection as to why these narratives hold such appeal to them.

Energy descent

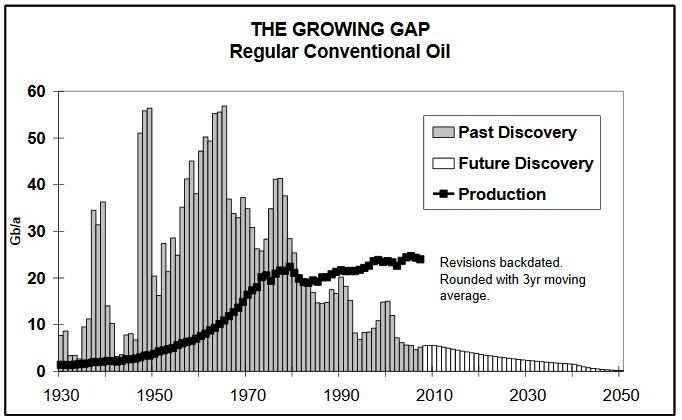

Permaculture thinking has explicitly hitched its wagon to one specific collapse model, based on energy descent and the theory of Peak Oil. I first came across Peak Oil in 2005 via a documentary featuring retired petroleum geologist Colin Campbell, based on his 1998 paper with Jean H. Laherrère entitled “The End of Cheap Oil” in Scientific American.

By the time I attended a live event at the University of South Australia with American researcher Richard Heinberg and David Holmgren in 2006, I was hooked on the Peak Oil narrative (for example, see: Habib 2008). Every day include a deep dive into the latest articles on the now-defunct EnergyBulletin.net website for the latest Peak Oil news. With high oil prices a factor in triggering the mortgage defaults in US suburbia that cascaded into the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis, Peak Oil seemed to be a looming boogie man that would initiate the systemic crisis that permies had been preparing for. In this bubble, it really did feel like we were headed toward the post-collapse agrarian dystopia of James Howard Kunstler’s World Made by Hand books.

Peak Oil as a concept seemed intuitively obvious; it refers to an approaching (or now past) peak of global oil production, first posited by M. King Hubbert in the 1950s. Hubbert proposed that the rate of discovery in individual oil fields followed a bell curve, at the halfway point of which rates of discovery would begin to decline (Hubbert 1956). As a consequence of this, at some point in the future the rate of production from a given field would also follow a bell curve congruent with the discovery curve. The peak of the production curve represented the point at which all the cheap and easily accessible oil form the field had been produced, with the remaining half consisting of oil of decreasing quality that would be increasingly expensive to extract.

The concept of the oil production bell curve is deceptively simple. Hubbert used his theory to predict that oil production from all fields in the United States would peak in 1970, which proved correct to within a year. He later extrapolated the peak principle to include all known global oil resources, coming to the prediction that the global oil peak would occur around 2000 (Hubbert 1956), though predictions for the timing of the global peak range from 2005 to 2030 (Deffeyes 2006; Ahlbrandt et al 2000). Peak Oil theorists argued that as demand for oil increased beyond the available supply as the peak is passed, the price of oil is likely to trend upwards, punctuated by volatile price swings. The impact of the peak on oil-dependent modern industrial societies was predicted to be severe, possibly resulting in disruption of agriculture and transportation, slowing down the wider global economy (Heinberg 2005; Roberts 2004).

“Permaculture has little faith in the capacity of renewable energy systems to provide sufficient energy for a globalised industrial culture. We are facing energy descent. Without fossil fuels, we cannot transport food and fertiliser to and from cities and a rural hinterland. Localisation is inevitable” (Leahy 2021).

“Rather than saying <inaudible>, I think they end up gonna say what it is at the moment rather than what it could be but I actually think economic contraction is one of those things that really makes people step on the ego, “I really got to do something different,” or, sadly, something cataclysms, some kind of political or economic or environmental – not disaster but something that makes everyone really <inaudible> like oil petrol shortage, where suddenly people would stop in their everyday life. I think that’s what it is. It’s the everyday life thing, not the bigger broader stuff, but something that affects people day to day. That really starts to touch people to go, “I have to make a change today because, otherwise, I can’t eat or I can’t get a work and if I can’t get to work, <inaudible>, so what I’m gonna do?” (Interviewee #26).

On this basis, permaculture practitioners argued for a contraction of economic activity to local community scale, in the belief that the world economy and transnational supply chains were doomed.

Insights and limitations of the Peak Oil narrative

The concept of Peak Oil blew my mind in the mid-2000s with its society-altering ramifications, but looking back from the perspective of 2025, how accurate has this theory been in its predictions about the world two decades on?

The theory of Peak Oil has been a contentious framework for understanding global energy transitions and geopolitics. It accurately highlighted some critical factors but also fell well short in explaining technological and geopolitical influences on the global energy system.

Peak Oil theory rightly underscored the geologic limits of fossil fuel production, predicting that oil extraction would reach a peak and decline due to resource depletion. This has resonated with historical production trends in regions like the U.S., where Hubbert’s prediction about conventional oil proved accurate (Kuhns et al 2018.). It effectively highlighted that rising production costs, coupled with declining oil field outputs, could incentivise shifts toward alternative energy (Fisher 2008). Peak Oiltheory also spurred discussions around energy security and renewable energy investments, underscoring its role in framing energy transitions as a matter of urgency (Buranaj Hoxha & Nair 2023).

The weaknesses of the Peak Oil theory stem from its overly deterministic and static assumptions about geology, technology, markets, and geopolitics, which we see reflected in permaculture’s energy descent scenario.

“Yes, our civilization is showing signs of stress, but the collapse I was promised back in my Peak Oil days was one in which the transportation, energy, financial and government infrastructure all stop functioning in short order. If I’m still getting emails from Bank of America telling me that my credit card payment is due, the collapse I once bought into has not happened. Wars? Growing disparities of wealth and opportunity? That’s the cyclical behavior of Capitalism, folks. The more history you read, the more familiar these patterns will become” (KMO 2022).

The theory paid limited attention to the role of geopolitics in shaping oil markets, such as OPEC’s influence, the emergence of new oil players, and the impact of sanctions (Solomon & Krishna 2011). For example, OPEC’s decisions, sanctions on oil-producing countries, and regional conflicts have profoundly impacted oil availability, often superseding geologic constraints (Solomon & Krishna 2011). Its primary focus on conventional oil resources and production in developed economies neglected the role of emerging markets. Also, the Paris Agreement, national climate change policies, and societal pressures to decarbonise economies were largely absent in the original Peak Oil framework, despite the fact that they have accelerated the transition to renewables and reduced fossil fuel demand, challenging the timeline and impact of peak oil scenarios (Draeger et al 2022).

By focusing heavily on geological factors, Peak Oil theory neglected market mechanisms like demand elasticity, price signals, and the development of alternative industries. High oil prices have historically incentivised energy efficiency and alternative energy investments, mitigating the feared abrupt decline in supply (De La Peña et al 2022). Peak Oil often oversimplified economic adaptability, as high oil prices triggered investments in renewable energy and efficiency, fundamentally altering demand curves (De La Peña et al 2022).

The theory treated energy transitions as linear and universal processes. However, transitions have been shown to vary significantly across regions, with some areas adopting renewables faster than others due to differing economic, technological, and policy conditions (Brannstrom et al 2022). Peak Oil assumed a static trajectory of oil consumption, underestimating the shifts in energy demand caused by urbanisation, digitisation, and changes in consumer behaviour. The rise of electric vehicles and energy-efficient technologies has reduced oil dependency more rapidly than anticipated by Peak Oil theorists, which American energy policy analyst Amory Lovins (2004) predicted in the early-2000s.

The theory did not fully address how economies adapt to scarcity. Peak Oil’s predictions underestimated the impact of technological innovations such as hydraulic fracturing, horizontal drilling, enhanced oil recovery, and deep-sea drilling. These advancements have significantly increased recoverable reserves, shifting the timeline of global peak oil (Caffentzis 2008). Renewable technologies, including solar and wind, have advanced more rapidly than expected, contributing to a slower decline in energy supply reliance on oil (Buranaj Hoxha & Nair 2023).

While Peak Oil accurately identified the finite nature of oil resources and sparked important discussions, its limitations highlight the complexity and adaptability of the global energy landscape. While Peak Oil has faded from view in serious energy system analyses (Bardi 2019), it lives on in the imagination of permaculture thinking on energy descent and the future prophesised by this scenario.

The collapse rainbow

The world we are living in 2025 is not the brand of collapse imagined by permies, Peakniks and doomers back in the mid-2000s. If we’re going to talk about collapse, we need to get clear on what exactly is collapsing (Brozović 2023). Are we talking about the collapse of states, hegemonies, economies, ecosystems, global society, or all of the above? The differences in frame of reference for collapse are important because they shape both the perceived causes and the proposed responses. Each framing implies different actors, solutions, and levels of intervention, influencing how individuals and communities prioritise their efforts.

Permaculture often assumes that societal and ecological collapse are inevitable due to the unsustainable nature of current systems, and the fossil fuel-based energy system in particular. Holmgren (2020) emphasises that openly accepting this inevitability fosters resilience planning and community preparation, while also recognising the potential for negative psychological effects, such as despair.

“I hesitate to use the word “Earth” because it sounds so hippy, but essentially, our survival existentially as species is gonna be dependent on us being able to reconnect with natural systems and realise that we are part of natural systems and that everything we do affects natural systems, and if we don’t look after those systems, then we will die. We’re getting to the point where our natural systems are so stressed that they’re starting to collapse, and a lot of people are still barely aware of that at all” (Interviewee #48).

The term “collapse” is nebulous, encompassing scenarios that range from gradual decline to abrupt systemic failure (Diamond 2005; Tainter 1988). The permaculture movement has embraced numerous collapse models, each with distinct assumptions and predictions. David Holmgren’s “energy descent” theory envisions a slow contraction of industrial society due to fossil fuel depletion (Holmgren 2009), while Dmitri Orlov’s “cliff model” depicts a sudden and catastrophic societal breakdown akin to the fall of the Soviet Union (Orlov 2008a).

“I think we’ve needed it all along. We just needed more and more – I think because the world is changing, the climate changes and more of an effect, because the people whose actually here and interestingly when you look at what people wrote about ten years ago, you can see changes, you can see the rise in fundamentalists and politics, the terrorism, that nationalism that people pulling back to their own selves and to look after themselves, that kind of thing” (Interviewee #26).

“Because the global problems are aggregating, getting more and more severe. Those things that were predicted 20 years ago to happen in around 2030 are actually happening now, like climate change, migration problems, soil crises, biodversity loss” (Interviewee #29).

Other models, such as “multi-scalar collapse,” emphasise the interconnectedness of local, national, and global breakdowns (Alexander 2013), while “uneven collapse” highlights the disproportionate effects on marginalised populations (Catton 1980). John Michael Greer (2008) argued that collapse is a prolonged iterative phenomenon, marked by crises followed by partial recovery, with each crisis reducing the need for maintenance, thereby temporarily stabilising the system. Greer identifies four facets of this collapse—declining energy availability, economic contraction, collapsing public health, and political turmoil—which are self-limiting in the short term but lead to ongoing cycles of crisis and recovery at progressively lower levels of organisation.

Permaculture’s co-founder David Holmgren (2014) has even advocated for an engineered collapse—”Crash on Demand”—to accelerate systemic transformation. The sheer diversity of these models underscores the profound uncertainty in forecasting collapse, rendering any singular adherence intellectually indefensible (Bardi 2017).

“I think there’s certainly politics within permaculture, ‘cause there’s people with big ideas about what it is and how it should work and how – and because it’s a scene and it evolves – you got doomsday preppers who are preparing for oil descent and bloody all sorts of chaos right up against the very proactive Vandana Shiva Seed Saving going with the – go for the light approach” (Interviewee #17).

Collapse does not unfold in a singular, universal fashion. The concept of uneven or layered collapse (Heinberg 2005) highlights that systemic breakdowns affect different regions, social classes, and sectors differently. Whyte (2017) critiques mainstream collapse narratives for their Eurocentric focus, pointing out that many communities—particularly Indigenous and marginalised groups—have already been experiencing forms of collapse for centuries due to colonialism, economic dispossession, and environmental degradation.

“And I think a lot of people feel, maybe in western societies at least, that seems a really pressing and important time in history, like this great complexity in the world. So, I think that some people, they have the opportunity, that’s a big part of their wanting to mobilise or do something” (Interviewee 21c).

Permaculture practitioners must be cautious about framing collapse as a sudden future event rather than an ongoing reality for many, recognising the ethical and political implications of their discourse.

Risks of prophetic collapse fixation

The allure of collapse narratives and the anticipation of large-scale societal downfall has fuelled a fixation on localist adaptation strategies in permaculture thinking. Localism is not problematic in and of itself, however, the preoccupation with localism as the only feasible response to crises manifests from a deterministic view of the future, wherein collapse is not merely possible but inevitable. In this distorted view, complex social, political and economic organisation is simply wished away, their existence an inevitable consequence of that collapse that requires little critical reflection.

Prophetic collapse perspectives can inspire proactive responses among some true believers. They also risk entrenching rigid worldviews that limit adaptability and prevent engagement with broader communities in developing systemic adaptations. At worst, they encourage dangerous quasi-accelerationist ideas (see David Holmgren’s “Crash on Demand” essay) and other ideas that are batshit crazy. Such ethically problematic positions disregard the immense human suffering collapse would entail, particularly for vulnerable populations.

“The adaptive response to collapse, should it prove necessary, will be emergent and organic. It will not be the result of your having picked the right belief system from among the many competing visions of the future battling it out on the Internet” (KMO 2022).

By critically examining the implications of prophetic collapse fixation, I argue for a more balanced, adaptive approach to permaculture thinking—one that acknowledges risks without being railroaded into specific future prophesies and succumbing to fatalistic determinism.

Think global, act local global

Permaculture often focuses on local resilience strategies, but mutli-scalar global crises—the polycrisis (Lawrence et al 2022)—require multi-scalar responses. Climate change, geopolitical instability, and economic crises are interconnected across local, national, and global levels (Lawrence et al 2022; Helbing 2013). While localised permaculture initiatives offer valuable models for sustainability, they cannot fully insulate communities from macro-level disruptions such as financial system shocks or climate-induced migration.

Permaculture presents itself as a holistic design framework for resilience, yet its efficacy as an adaptation strategy is contingent upon the nature and scale of the collapse scenario in question. While permaculture principles emphasise ecosystemic stability, regenerative practices, and local self-sufficiency (Mollison & Holmgren 1978), their applicability varies depending on the type of disruption (gradual decline, systemic shock, partial breakdown, or full-scale collapse) and scale of disruption (local, regional, national, or global).

For energy descent scenarios, permaculture is well-aligned, as its emphasis on decentralised, low-energy food production and sustainable land management directly addresses the vulnerabilities of fossil fuel dependency (Holmgren 2009; Astyk & Newton 2009). In such contexts, agroecological practices and closed-loop resource cycles offer viable alternatives to industrial agriculture and centralised supply chains (Ferguson & Lovell 2019).

“Amidst a changing climate, natural disasters, peak oil and political disaffection, permaculture offers practical ways to combat issues of food and energy security as well as ways for people to reconnect with the land and their communities” (Interviewee #34).

Several interviewees questioned the feasibility of global responses to collapse, instead emphasising localism and decentralisation. This idea that globalisation may retract, leading to fragmented enclaves, aligns with predictions made by Dmitri Orlov (2008) and James Howard Kunstler (2005) about localised resilience replacing large-scale economic and political networks.

“The transformative potential – I don’t know. I don’t see the future as a global thing. I think climate change is gonna make us very much an – possibly transform the world into just a bunch of enclaves and globalisation having to retract its web through needs, but then it’s like, “On what time scale is that and can there be a global movement before those sort of things happen?” (Interviewee #19).

Similarly, some practitioners suggest that climate change and systemic breakdowns will make permaculture more relevant because it enables local adaptation to resource scarcity and economic contraction. However, the uncertainty over whether global movements can act before collapse occurs suggests scepticism about large-scale coordination.

“Yes, human nature is the biggest one. I think mainstream Australia, mainstream everywhere is still resistant to changing their habits and their lifestyles for a sustainable future. So if you’re trying to sell less, it’s gonna be a hard sell when you’re up against economies, energies, fossil fuels, governments, corporate greed. If it’s permaculture against all that – don’t really stand a chance, but at least there was a fight, at least they were involved. But when the shit gets so bad that those things do crumble that more is not an option, that when you can’t breathe or when you can’t eat, there is a solution that you can go for. That said, you can go for a long time without breathing like in China and you can go for a long time in Kolkata living in each other’s lunch and like 20 million people in each other’s face before you actually get to the searching for the solutions. So, if they’re representatives of how far the world will go into its own demise before it starts finding solutions, it’s not that good. So you actually do need to convert the people who you’re trying to sell less to before it gets completely fucked, ‘cause if you’re waiting for the collapse, it’s too late. And collapse will go really dark. It gets dark like the poverty or the pollution can go really deep before you sort it out. So, the final answer is permaculture does need to be more proactive rather than just a solution that people come and look for, because by the time they come and look for it, it’s too late” (Interviewee #17).

However, in scenarios involving rapid geopolitical or economic collapse, permaculture’s localised focus may present limitations. Large-scale financial shocks and political instability often disrupt property rights, trade, and governance structures, rendering small-scale agrarian solutions insufficient without broader institutional safeguards (Scott 2009; Tainter 1988). For instance, case studies of economic collapse in Venezuela and Zimbabwe highlight the importance of social capital, market access, and legal protections, factors that permaculture alone cannot guarantee (Cannon 2000; Richardson 2004).

Moreover, in scenarios of mass migration and conflict, security concerns and shifting demographics may challenge the feasibility of long-term land-based resilience strategies (Dalby 2013b; Homer-Dixon 2006). Permaculture is also less equipped to address technological or cybernetic collapse scenarios, where disruptions to digital infrastructure, communication networks, and data systems may present existential risks (Harari 2018; Morozov 2012).

While permaculture emphasises biological resilience, it offers limited ideas about the interplay of complex medical, financial, and industrial systems in adaptation and resilience-building (Bostrom 2014; Tainter & Patzek 2012). Nevertheless, permaculture offers useful resilience tools when integrated with broader socio-political and economic strategies (Folke et al 2010; Pelling 2011). Acknowledging these limitations fosters a more balanced perspective, encouraging practitioners to work both within and outside existing institutions to build resilience at multiple levels.

Scenario bias

Effective crisis preparedness demands adaptability (Folke et al 2010; Carpenter et al 2001). So when permies allocate all their resources toward one anticipated scenario, they can compromise their ability to navigate alternative futures (Homer-Dixon 2006). A group investing exclusively in off-grid living to counteract fossil fuel decline, for example, may be blindsided by financial collapse, migration crises, political upheaval, or a global pandemic that would be more constructively addressed through networked adaptations at scale (Dalby 2013a).

“So, we’re not thinking early enough and creatively enough. This is where I like to be a little bit in the forefront of what we need to be doing now for the future we think we’re creating. One of them is create the models, live it, and the third thing get the future in your head and start offering solutions now” (Interviewee #1).

As I’ve argued earlier in this article series, an overemphasis on self-sufficiency can lead to an underestimation of the importance of broader social and economic networks (Adger 2003; Pelling 2011). Contrary to the belief that isolation is key to survival, history suggests that mutual aid, community collaboration, and adaptive economies are far more reliable survival mechanisms (Scott 2009), and all of those things are found more abundantly in cities.

“The Doomer prescription is to get away from the cites. Learn to grow food and make due without the technological conveniences of petroleum-powered civilization. This will put you in a resilient position when the lights go out and the starving hoards pour out of the cities on foot in search of their next meal. It gets under my skin to hear Boomer Doomers dispense this advice to young people. Those Boomers, more often than not, built their capital within the System that they now imagine is collapsing. If you go out to the countryside with capital, you can build your Doomstead and operate as a sort of futile lord who commands the cheap labor of young people lured out to the sticks WITHOUT sufficient capital. If you go out there young and broke, you will be a serf to someone who went out there WITH capital” (KMO 2022).

History offers numerous examples of societies that have faced severe crises but adapted rather than collapsed entirely. In his classic book The Collapse of Complex Societies, Joseph Tainter (1988) highlights that complexity can be restructured rather than merely lost, suggesting that collapse is often a process of transformation rather than total disintegration (Peakniks tend to disregard those chapters in Tainter’s book). The post-World War II reconstruction of Europe, the rapid adaptation to financial crises, and the resilience of social safety nets during economic downturns demonstrate that human societies are capable of significant recovery and adaptation. Permaculture’s emphasis on localism and decentralisation must therefore be tempered with an awareness of the role that institutions, global cooperation, and technological progress can play in mitigating systemic risks (Helbing 2013).

Blinkered rigidity

People who think they know exactly what the future looks like will make mistakes. A singular fixation on one collapse prophecy fosters epistemological rigidity—an intellectual straitjacket that stifles adaptation (Taleb 2012; Holling & Gunderson 2002). The history of failed predictions serves as a cautionary tale: from Malthusian overpopulation crises that never materialised (Simon 1981; Ehrlich 1971) to Peak Oil forecasts that disregarded technological advances (Smil 2014; Rapier 2012), errors which stemmed from an inability to factor in the dynamic nature of technological, economic, and social systems.

The Peak Oil movement, for instance, catastrophically underestimated fracking and renewable energy advances, leading to inaccurate policy and investment prognostications (Bridge 2015).

“Yeah, but it’s easy to get into a place of complete stagnation. Like I recall when I first started getting savvy to Peak oil, I was kind of going, “Yey!” <laughs> I was like, finally, something that’s actually going to put the brakes on and make us have to come to terms with stuff but there’s a risk in that too, because then there’s nothing – you kind of lose faith in humanity and any ability of us to actually think clearly about stuff and to affect the people around us. You can be going, “Oh, let’s wait for the brick wall” and we’ll hit the brick wall and then we’ll pick up the pieces” (Interviewee #22).

Rigid adherence to a particular collapse model results in strategic myopia (Walker & Salt 2006). By overcommitting to a specific vision, permies risk leaving themselves vulnerable to other, unforeseen crises, whether geopolitical, economic, or climate-induced (Rockström et al 2009).

Psychological maladaptation

Collapse narratives exert powerful psychological effects (Beck 1992). While an awareness of crisis can spur action, it can also induce paranoia, fatalism, and collective hysteria (Turner & Pidgeon 1997). Movements that structure their identities around imminent catastrophe risk alienating themselves from reality, fostering nihilism or a slide into conspiracism, instead of building constructive resilience (Kunstler 2005; Greer 2011).

“Doomers will ridicule non-Doomers as “sheeple,” a word also used by conspiracy theorists to set themselves apart from the uncritical drones of society who believe all the comforting myths about the benevolence of government and the institutions of science and finance. The idea that you can see through all of the fanciful set decoration of this Potemkin village of a civilization right down to its cancerous, rotten core means that you have the intellectual and moral courage to face reality. That sets you apart as superior to people who don’t hold your dim view of civilization and humanity. They might have better careers and family lives, but you see how meaningless all of that is, and you eschew the contemptable “hopium” that the sheeple imbibe day in and day out which allows them to continue to believe that this deplorable civilization has any sort of future” (KMO 2022).

Many interviewees express frustration, despair, and existential distress about the trajectory of global systems. The perception of a “bombarded world” and the feeling that people are “plenty disillusioned” suggest a widespread sense of alienation. Interviewees describe a mounting wave of frustration and despair, linking their engagement with permaculture to an attempt to find meaning and agency in the face of systemic decline. This aligns with broader eco-anxiety discourse, in which concerns about environmental and social crises contribute to psychological stress (Kieft 2021).

“We rarely talk about what’s wrong with the world. We don’t actually – there’s a shitload wrong with the world and there’s – but we know that people know that. It’s not through lack of disillusionment with the way that the world works that people don’t make change. People are plenty disillusioned, but if they feel disillusioned and disempowered to make change, they don’t do anything at all. They just get depressed and they’re onto medication and they just tune into the box or to the screen, tune in to the sugar, tune in to the alcohol, tune in to the antidepressants, and tune out to real social connection and real connection to nature. So, we can’t have that. We need to make sure that we provide those pathways” (Interviewee #16).

“It’s hard to get a toehold in this sort of bombarded world, but it’s also the fact that people’s way of thinking is very faddish. It’s like what’s cool now, what’s groovy now, and then in six months’ time, that’s not cool anymore. I think underneath that, there is an incredible wave of frustration, and despair, and distress that’s starting to well up in our society, which is one of the reasons why I turned to permaculture” (Interviewee #48).

However, some interviewees push back against over-emphasising crisis, warning that excessive focus on collapse can lead to disempowerment rather than action. There is an underlying tension between acknowledging the severity of global issues and maintaining a sense of hope and agency (Baker 2013).

It is not healthy to get stuck on such a negative emotional pitch. A deterministic collapse mindset can foster fatalism, undermining proactive adaptation and engagement with reformist solutions. Dmitri Orlov’s (2008b) staged model of collapse, which assumes sequential breakdowns of financial, political, and social institutions, ends up being disempowering for individuals who feel that large-scale collapse is inevitable and therefore not worth resisting. This manifests a feedback loop in which permies already disengaged from mainstream political and economic structures end up seeking further escape (Roux-Rosier et al 2018).

“But it’s easy to get locked into a space where you’ve actually lost faith in our ability to do anything and I often sit in that space. It’s a healthy space to be in, but you can’t dwell on it. You have to go forward with some kind of – No, it’s not, and it leaves you going – well, actually, even the survivalists are entirely wrong, because if it really is all gonna fall in a screaming heap, then it really comes down to who’s got the biggest gun for the few days when the chips are down, it’s like – <laughs> Yeah, exactly. It’s pretty unhealthy and it’s pretty stultifying in how do you get on with stuff, how do you live within your society, how do you operate in your community, what do you do?” (Interviewee #22).

The obsessive commitment to the collapse prophesy can also erode the public engagement permaculture needs in order to grow. The apocalyptic rhetoric normalised in the collapse narrative as the inevitable endpoint alienates audiences beyond permaculture, positioning the movement as a fringe cult rather than a viable framework for sustainable adaptation (Latour 2018; Jasanoff 2004). By appearing more preoccupied with validating their prophecies than offering pragmatic solutions, permies risk undermining their own credibility (Dryzek 2022).

Permaculture refugees

The arc of my participation in the permaculture movement bends from ecstatic discovery of permaculture as a safe haven from the mainstream, to where I am now as a disappointed and deflated refugee from the permaculture movement. The misgivings I had about the quaint rural localism of the escapist permaculture “dream” were initially manageable. But when the COVID pandemic came around and the worst aspects of permaculture escapism were exposed by the selfish individualism and idiotic conspiracism of some of its big names (Grayson 2023), I knew my time in the movement was up.

I’m far from alone in falling out of love with permaculture. The video above by American podcaster KMO, whose content on Peak Oil and his dalliances with permaculture on his C-Realm Podcast in the mid-2000s to early-2010s were influential in the sub-culture, echoes my arc in how he became jaded by the failed promises and false prophesies of the energy descent collapse narrative.

KMO notes how the collapse narrative is as much a projection of fears, insecurities and traumas of those who embrace it:

“The psychological elements became clear — I adopted the Doomer mindset at a time of personal financial distress. The idea that the whole oppressive apparatus of industrial capitalism would soon collapse promised an escape from the unrelenting pressure to make money. I didn’t see myself as engaging in wishful thinking at the time. The prospect of collapse was genuinely terrifying to me, but it was the thrilling experience of terror that we seek in horror movies and on roller-coasters. The longer I spent in the collapse community, the more I noticed that the people predicting collapse almost always held an extremely dim view of contemporary civilization. They fostered longstanding gripes of a political, economic or spiritual nature. “I hope I’m wrong about the coming collapse,” they’d say, but it seems to me they were secretly longing for it because they thought it represented justice. They wanted to see the powerful brought down for their greed and short-sightedness and their willingness to get rich at the expense of the natural world” (KMO 2022).

That was me too. When I imbibed the collapse prophesy, I was at a place in my life where I was economically and emotionally insecure, well before I embarked on my grand journey of self-exploration into mental health and discovery of my neurodifference. The collapse narrative fed on my insecurity, feeding my unconscious people-pleasing tendencies with purpose as a collapse evangelist and martyr, and feeding my repressed trauma with the schadenfreude of watching the society that hurt me eventually eat itself. That is not a healthy place from which to manifest social and environmental justice.

Need for epistemological humility

The lesson here is that the energy descent collapse prophesy is orders of magnitude too simple to explain and predict the future of a world of inter-related complex ecological, political, economic and social systems. History demonstrates that societies, economies, and ecosystems do not follow linear or uniform trajectories. Permaculture practitioners should exercise epistemological humility around collapse because of the inherent complexity, unpredictability, and contingency of large-scale change.

Overconfidence in particular collapse scenarios create a confirmation bias that risks intellectual rigidity, ethical missteps, and practical inefficacy. By embracing epistemological humility, practitioners can remain open to uncertainty, alternative pathways, and the possibility of resilience or transformation beyond the collapse frameworks they currently envisage.

“I haven’t stopped trying to make sense of the human predicament at the big picture level. I’m now just a lot stingier with my ideological commitments. I hold my opinions lightly, and ultimately, I’m most interested in pursuing activities that put me in satisfying interaction with other people” (KMO 2022).

A sounder approach to uncertainty demands epistemological humility—the recognition that no one can definitively predict the trajectory of systemic change (Scoones 2019; Stirling 2010). Rather than clinging to a single collapse narrative, permaculture practitioners should embrace scenario planning and dynamic adaptation (Munasinghe & Swart 2005).

“One of the sillier notions that has circulated within the permaculture milieu is that non-experts know more than people who have spent years studying and working in a field. This just makes permaculture look ridiculous” (Grayson 2023),

Epistemological humility requires acknowledging that the consequences of systemic collapse are not easily predictable and that advocating for collapse as an end in itself is both ethically fraught and practically dubious. A naive belief that collapse will “reset” society in a beneficial way overlooks historical precedents where social breakdowns have led to authoritarianism, resource conflicts, and exacerbated inequalities (Rotberg 2003).

Scenario planning, a strategic foresight method, offers a more rational framework for managing uncertainty (Schwartz 2012). By contemplating multiple potential futures—ranging from collapse to renewal—communities can foster resilience without succumbing to ideological fixation (Sellberg et al 2018). This approach ensures preparedness without entrenching dogma, allowing movements to evolve as conditions change (Berkhout et al 2002).

Over and out.

Permaculture offers a promising framework for addressing some aspects of the global polycrisis, but its capacity to address the full scope of this moment is limited. The interconnected economic, environmental, political, and social challenges of our time require multifaceted solutions that go beyond what permaculture alone can provide.

Permaculture’s strength lies in its ability to create sustainable, regenerative agricultural systems that can help mitigate environmental degradation and promote local resilience. Its emphasis on designing systems that mimic natural ecosystems can enhance food security, conserve resources, and reduce waste. Additionally, permaculture promotes community-based solutions and local cooperation, which in and of itself is never a bad thing.

However, permaculture is not a panacea. The global polycrisis involves deep-seated systemic challenges that require coordinated global efforts, policy changes, and economic restructuring. While permaculture can support these broader efforts, it does not and cannot address issues such as the concentration of wealth and power, systemic inequality, or the geopolitics that fuel many of the crises in the first place.

The purpose of my research project, my contributions to permaculture thinking since 2014, and this article series, is to argue that permaculture can play a role in addressing environmental, economic and social dimensions of the global polycrisis, but, to actualise its ethical commitments the permaculture movement needs to be part of a broader, more integrated approach that tackles economic, political, and systemic issues at a transnational scale.

As for me, this article represents the end of the road for my participation in the permaculture movement. There are many great insights and warm moments I take from my time with permaculture, and I hope my contribution to the movement has been a useful one. Permaculture provided me with what I needed at the time I found it, but that need has long passed its time now to move on.

References

Adger, W. N. (2003). Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Economic Geography. 79(4), 387-404.

Ahlbrandt, T., Charpentier, R., Klett, T., Schmoker, J., & Schenk, C. (2000). World Petroleum Assessment 2000: Analysis of Assessment Results. United State Department of the Interior and United States Geological Survey.

Alexander, S. (2013). Entropia: Life Beyond Industrial Civilisation. Simplicity Institute.

Astyk, S. & Newton, A. (2009). A Nation of Farmers: Defeating the Food Crisis on American Soil. New Society Publishers.

Baker, C. (2013). Collapsing Consciously: Transformative Truths for Turbulent Times. North Atlantic Books.

Bardi, U. (2017). The Seneca Effect: Why Growth is Slow but Collapse is Rapid. Springer.

Bardi, U. (2019). Peak oil 20 years later: Failed prediction or useful insight? Energy Research & Social Science. 48, 257-261.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. SAGE.

Berkhout, F., Hertin, J., & Jordan, A. (2002). Socio-economic futures in climate change impact assessment: using scenarios as ‘learning machines’. Global Environmental Change. 12(2), 83-95.

Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press.

Bridge, G. (2015). Energy (in)security: World-making in an age of scarcity. The Geographical Journal, 181(4), 328-339.

Brozović, D. (2023). Societal collapse: A literature review. Futures. 145, 103075.

Caffentzis, G. (2008). The Peak Oil Complex, Commodity Fetishism, and Class Struggle. Rethinking Marxism. 20.

Campbell, C. J., & Laherrère, J. H. (1998). The End of Cheap Oil. Scientific American. 278(3), 78–83.

Cannon, T. (2000). Vulnerability analysis and disasters. In Parker, D. J. (Ed.). Floods. Routledge, 43-55.

Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Anderies, J. M., & Abel, N. (2001). From metaphor to measurement: resilience of what to what? Ecosystems. 4(8), 765-781.

Catton, W. R. (1980). Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. University of Illinois Press.

Cooper, D. (2014). Everyday Utopias: The Conceptual Life of Promising Spaces. Duke University Press.

Dalby, S. (2013a). Security and Environmental Change. Polity Press.

Dalby, S. (2013b). The geopolitics of climate change. Political Geography. 37, 38-47.

Deffeyes, K. S. (2006). Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert’s Peak. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Penguin.

Dryzek, J. S. (2022). The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses (4th Ed.). Oxford University Press.

Ehrlich, P. R. (1971). The Population Bomb. Buccaneer Books.

Ferguson R. S. & Lovell S. T. (2019). Diversification and labor productivity on US permaculture farms. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems. 34(4), 326-337.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, F. S., & Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability, and transformability. Ecology and Society. 15(4) 20.

Grayson, R. (2023). Fractures and healing: how do we move beyond permaculture’s disagreement? Medium.

Greer, J. M. (2011). The Wealth of Nature: Economics as if Survival Mattered. New Society Publishers.

Greer, J. M. (2008). The Long Descent: A Users Guide to the End of the Industrial Age. New Society Publishers.

Habib, B. (2008). The Perceptions of climate change and peak oil among Flinders University students and their receptiveness to individualist lifestyle changes and mitigation strategies. 3rd Annual Solar Cities Congress, Adelaide, Australia.

Harari, Y. N. (2018). 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Spiegel & Grau.

Heinberg, R. (2005). The Party’s Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies. New Society Publishers.

Helbing, D. (2013). Globally networked risks and how to respond. Nature. 497(7447), 51–59.

Holling, C. S. & Gunderson, L. H. (2002). Resilience and adaptive cycles. In Gunderson, L. H. & Holling, C. S. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Island Press, 25-62.

Holmgren, D. (2020). Essence of Permaculture: Revised Edition. Melliodora Publishing.

Holmgren, D. (2014). Crash on Demand: Welcome to the Brown Tech Future. Holmgren Permaculture Vision and Innovation.

Holmgren, D. (2009). Future Scenarios: How Communities Can Adapt to Peak Oil and Climate Change. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Homer-Dixon, T. (2006). The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity, and the Renewal of Civilization. Island Press.

Hubbert, M. K. (1956). Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels. Shell Development Company, Exploration and Production Research Division.

Jasanoff, S. (2004). States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. Routledge.

Kieft, J. (2021). The responsibility of communicating difficult truths about climate influenced societal disruption and collapse: An introduction to psychological research: A literature review. Ata: Journal of Psychotherapy Aotearoa New Zealand. 25(1), 55-87.

KMO. (2022). I used to be a doomer. Medium.

Kuhns, R. J. & Shaw, G. H. (2018). Peak Oil and Petroleum Energy Resources. In R. J. Kuhns & G. H. Shaw (Eds.). Navigating the Energy Maze: The Transition to a Sustainable Future. Springer International Publishing, 53-63.

Kunstler, J. H. (2005). The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Kunstler, J. H. (2009). World Made by Hand. Grove Press.

Latour, B. (2018). Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Polity Press.

Lawrence, M., Janzwood, S., & Homer-Dixon, T. (2022). What Is a Global Polycrisis? And how is it different from a systemic risk?(Version 2.0). Discussion Paper 2022-4. Cascade Institute.

Lovins, A. B. (2004). Winning the Oil Endgame: Innovation for Profits, Jobs and Security. Rocky Mountain Institute.

Mollison, B. C., Holmgren, D. (1978). Permaculture 1: A Perennial Agricultural System for Human Settlements. Transworld Publishers.

Morozov, E. (2012). The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. PublicAffairs.

Munasinghe, M. & Swart, R. (2005). Primer on Climate Change and Sustainable Development: Facts, Policy Analysis, and Applications. Cambridge University Press.

Orlov, D. (2008a). Reinventing Collapse: The Soviet Example and American Prospects. New Society Publishers.

Orlov, D. (2008b). The Five Stages of Collapse. Resilience.org.

Pelling, M. (2011). Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation. Routledge.

Rapier, R. (2012). Power Plays: Energy Options in the Age of Peak Oil. Apress.

Richardson, C. (2004). The Loss of Property Rights and the Collapse of Zimbabwe. Cato Journal. 25.

Roberts, P. (2004). The end of oil: On the edge of a perilous new world. Houghton Mifflin.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K. et al. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 461(7263), 472–475.

Rotberg, R. I. (2003). Failed States, Collapsed States, Weak States: Causes and Indicators. In R. I. Rotberg (Ed.). State Failure and State Weakness in a Time of Terror. Brookings Institution Press, 1–26.

Roux-Rosier, A., Azambuja, R., & Islam, G. (2018). Alternative visions: Permaculture as imaginaries of the Anthropocene. Organization. 25(4), 550-572.

Schwartz, P. (2012). The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World. Crown.

Simon, J. L. (1981). The Ultimate Resource. Princeton University Press.

Scott, J. C. (2009). The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press.

Sellberg, M. M., Ryan, P., Borgström, S. T., Norström, A. V., & Peterson, G. D. (2018). From resilience thinking to Resilience Planning: Lessons from practice. Journal of Environmental Management, 217, 906-918.

Smil, V. (2014). A Global Transition to Renewable Energy Will Take Many Decades. Scientific American. January 2014.

Stirling, A. (2010). Keep it complex. Nature. 468, 1029–103.

Tainter, J. A. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Tainter, J. A. & Patzek, T. W. (2012). Drilling down: The Gulf oil debacle and our energy dilemma. Springer Science & Business Media.

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. Random House.

Turner, B. A., Pidgeon, N. F. (1997). Man-made disasters. Elsevier Science & Technology Books.

Walker, B. & Salt, D. (2006). Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Island Press.

Whyte, K. (2017). Indigenous climate change studies: Indigenizing futures, decolonizing the Anthropocene. English Language Notes. 55(1–2), 153–162.

[…] X. Collapse prophesies. […]