- RATIONALE

- BRIEFING NOTES

- LEARNING ACTIVITY

- Learning objectives

- Methodology for case study analysis using the concentric circles model

- Step 1: Choose a case study

- Step 2: Define the core interests of the case study state

- Step 3: Map the first circle (immediate neighbours)

- Step 4: Examine the second circle (strategic allies and key partners)

- Step 5: Analyse the third circle (global engagement)

- Step 6: Contextualise the findings

- Step 7: Evaluate the model’s applicability

- Step 8: Develop case study conclusions

- References

Foreign policy is often a balancing act in which states must carefully allocate their diplomatic, economic, and military resources to safeguard their core interests while engaging with the wider world. To make sense of these complexities, scholars and policymakers use conceptual frameworks to organise foreign policy priorities. One such framework is the concentric circles model, which structures a state’s international engagement into hierarchical layers, ranging from immediate national concerns to global ambitions.

In this article, the briefing notes explore the model’s theoretical foundations, its application in foreign policy analysis, and its strengths and limitations. The article then presents a structured learning activity for undergraduate students of International Relations, which provides a step-by-step methodology for students to use in analysing a state case study using the concentric rings model. This activity will help students to develop both theoretical knowledge and practical analytical skills for understanding foreign policy in a structured and comparative way.

RATIONALE

Undergraduate students of International Relations should learn to use the concentric circles model as a heuristic for foreign policy analysis because it:

- Provides a structured framework, helping students to categorise foreign policy priorities into logical layers, making complex international relations more manageable.

- Enhances strategic thinking, encouraging students to analyse how states allocate diplomatic, economic, and military resources based on proximity and strategic importance.

- Develops comparative analysis skills, allowing students to compare different the foreign policies of different states by identifying patterns and variations in their concentric circles.

- Bridges theory and practice in connecting core IR theories (realism, geopolitics, constructivism) with real-world foreign policy decisions.

- Improves policy evaluation abilities by encouraging students to think critically about the effectiveness and limitations of foreign policy strategies within different layers of engagement.

- Helps students understand middle and regional powers by analysing how states with limited global reach prioritise their international engagements.

- Can be applied across different case studies and used with versatility to analyse great powers, middle powers and small states.

- Highlights the role of geography and security, reinforcing the importance of geopolitical constraints and regional security dynamics in shaping state behaviour.

- Encourages awareness of multilateral diplomacy, showing how states balance national interests with regional and global commitments in institutions like the UN, ASEAN, or the G20.

- Supports academic and professional skills, helping students to prepare for careers in foreign policy and international affairs.

BRIEFING NOTES

The concentric circles model of foreign policy is a well-established heuristic in International Relations, providing a structured way of understanding how states prioritise their external engagements based on proximity and strategic significance. Frequently associated with British foreign policy (Bayne & Woolcock 2017), it has also been applied in analyses of regional powers and middle states (Hill 2015; Gambari 1989).

The concentric circles

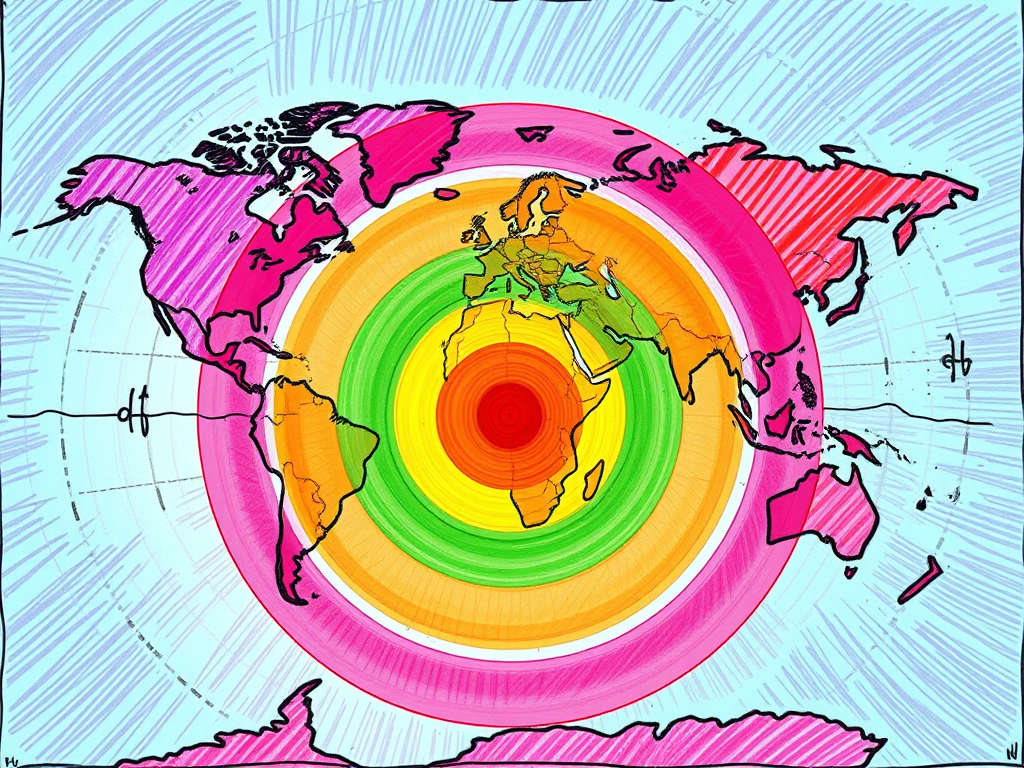

The model posits that foreign policy operates in hierarchical layers, with the innermost circle comprising core national interests, such as territorial security and key bilateral relationships, while the outer circles encompass wider geopolitical and multilateral concerns (Buzan & Wæver 2003).

Innermost circle: Core national interests. At the centre of the concentric circles are the state’s core interests, including sovereignty, territorial integrity, political stability, and the welfare of its citizens. The policies in this circle focus on preserving the state’s existence and maintaining internal security.

Second circle: Immediate neighbours. This layer includes countries that share borders or are geographically close. Relations in this circle often prioritise regional stability, trade, and security cooperation, as instability in neighbouring countries can spill over into the core.

Third circle: Strategic partners and key allies. This layer encompasses alliances and partnerships that are not geographically immediate but are strategically vital for political, economic, or military reasons. Policies in this circle may involve trade agreements, defence partnerships, or shared political ideologies.

Fourth circle: Global and multilateral engagements. This outermost circle focuses on the state’s role in global governance, international organisations, and broader global concerns like climate change, humanitarian aid, or peacekeeping. The engagement here reflects the country’s aspirations for influence and leadership in the international community.

The concentric circles model aligns with realist and geopolitical traditions, emphasising hierarchy and proximity in international relations. Buzan and Wæver (2003) underscore how states prioritise threats and alliances within their immediate geographic vicinity before addressing distant global concerns. Similarly, Hill (2003) argues that states naturally allocate diplomatic and military resources first to “zones of primary interest,” often proximate regions critical to national security.

The concentric circles model as a heuristic

The concentric circles model serves as a practical heuristic for policymakers and analysts, offering a means of organising and prioritising foreign policy commitments. Heuristics in International Relations simplify complex realities, enabling decision-makers to allocate resources efficiently and formulate strategic approaches based on a structured framework (Jervis 2017). The model provides a useful mental map, particularly for states navigating multiple geopolitical challenges simultaneously.

One of its key advantages is its ability to clarify the relative importance of different foreign policy arenas. By distinguishing between core, regional, and global concerns, the model helps states avoid overstretch and maintain focus on immediate strategic imperatives (Mearsheimer 2001). This is particularly relevant for middle powers, which must balance their commitments without the global reach of great powers (Cooper 2016; Jordaan 2003). However, the heuristic nature of the model also means that its application is necessarily flexible, with circles overlapping and shifting according to changing geopolitical contexts (Nexon 2009; Ruggie 2002).

Critiques of the concentric circles model

Despite its utility, the concentric circles model is not without limitations. Real-world foreign policy decisions often overlap or defy clear boundaries. The model focuses heavily on state-centric interactions, potentially underestimating the influence of multinational corporations or international NGOs. Also, the weight of each circle can vary depending on leadership or circumstances, leading to inconsistencies.

Ikenberry (2019) and Nye (2020) suggest that the rigid hierarchical structure proposed by concentric circles is increasingly undermined by transnational interdependencies, economic globalisation and the growing influence of non-state actors. Economic diplomacy does not always follow geopolitical logic, leading some scholars to argue that state interests are more diffuse and networked than the model suggests (Keohane 2005). However, others, such as Cohen (2019) and Kirshner (2014), maintain that economic strategy still aligns with concentric principles, as illustrated by China’s Belt and Road Initiative, where investment patterns mirror an inner core of vital economic interests and looser commitments in more peripheral regions (Shambaugh 2013).

Constructivist scholars challenge its state-centric assumptions, arguing that foreign policy is often shaped by normative and ideational factors rather than merely strategic calculations (Finnemore & Sikkink 2001; Acharya 2018). Postcolonial critiques highlight its Eurocentric underpinnings, particularly in its application to former imperial states (Hobson 2012; Grovogui 2016). Feminist perspectives further interrogate the model’s embedded power hierarchies, questioning its implicit assumptions about state agency and influence (Enloe 2014; True 2019).

Nonetheless, the concentric circles model offers a pragmatic lens for understanding how states navigate complex international environments by systematically prioritising engagements. While critics argue it risks oversimplifying interdependencies in globalisation, its value as a heuristic for IR students lies in illuminating how states balance limited resources with layered interests. By integrating geographic, cultural, and strategic variables, the model remains a useful tool in learning the craft of foreign policy analysis.

LEARNING ACTIVITY

The concentric circles model of foreign policy provides a structured heuristic to analyse a state’s international relations, by categorising its priorities and engagements across layers of influence and proximity.

Learning objectives

By completing this case study, students should be able to:

- Demonstrate a structured understanding of how states prioritise their foreign policy objectives.

- Analyse the regional and global engagements of their chosen state with reference to security, trade, and diplomacy.

- Apply the concentric circles model to assess and compare foreign policy strategies across different states.

- Communicate a coherent, well-supported analysis in both written and verbal formats.

Methodology for case study analysis using the concentric circles model

The following methodology outlines the key steps and analytical tools required for students to apply this model to their chosen case study state. This activity should ideally be completed in class by students in small groups of 3-4, with each group compiling a cumulative body of outputs culminating with groups making an assessable group presentation, and students submitting an individually researched briefing paper on their case study findings.

Step 1: Choose a case study

Each group chooses a state to analyse as their concentric circles case study.

Step 2: Define the core interests of the case study state

Identify your case study state’s innermost concerns and imperatives: Review foundational documents (e.g., constitutions, national security strategies, key political speeches). Analyse domestic policy priorities and political rhetoric. Examine economic indicators, defence spending, and critical domestic challenges.

Questions to address:

- What are the state’s fundamental objectives (e.g., regime survival, economic stability)?

- Which domestic pressures (e.g., resource scarcity, internal conflicts) shape its foreign policy?

- How do historical or cultural factors inform these priorities?

Outputs: Develop a list of core state interests, with descriptions of how these interests shape foreign policy decisions.

Step 3: Map the first circle (immediate neighbours)

Analyse the state’s relationships with neighbouring countries or geographically proximate entities: Study bilateral treaties, trade agreements, and military alliances with neighbours. Examine historical conflicts, border disputes, or cooperative initiatives. Utilise geographic information systems (GIS) to visualise regional connections.

Questions to address:

- How does the state manage its borders and relationships with immediate neighbours?

- What role do neighbours play in ensuring (or threatening) the state’s core interests?

- Are there shared resources or regional organisations influencing these relations?

Outputs: Compile a map of bilateral and regional relationships, including an assessment of threats and opportunities in the immediate neighbourhood.

Step 4: Examine the second circle (strategic allies and key partners)

Understand the state’s relations with allies and influential partners beyond its immediate neighbourhood: Identify economic, military, and diplomatic alliances (e.g., NATO, ASEAN). Study trade flows, foreign direct investments, and cultural exchanges. Review participation in defence or strategic agreements.

Questions to address:

- Who are your case study state’s most critical allies and partners, and why?

- How do these relationships enhance the state’s economic and military security?

- Are these relationships transactional, ideological, or historical?

Outputs: Draw a network diagram showing connections with strategic allies and provide an analysis of the benefits and challenges of these partnerships.

Step 5: Analyse the third circle (global engagement)

Assess the state’s role and behaviour within the global system: Evaluate participation in international organisations (e.g., UN, WTO, IMF). Analyse contributions to global challenges (e.g., climate change, peacekeeping). Study foreign policy speeches and global public diplomacy efforts.

Questions to address:

- What is the state’s vision for its global role (e.g., great power, regional leader)?

- How does it engage with multilateral institutions and global norms?

- What soft power tools (e.g., cultural diplomacy, media) does it employ?

Outputs: Identify a narrative of the state’s global ambitions and constraints and provide an assessment of how its global engagement aligns with its core interests.

Step 6: Contextualise the findings

Place the state’s foreign policy within its broader historical, cultural, and systemic context: Review historical legacies (e.g., colonialism, wars, revolutions). Analyse regional and global power dynamics (e.g., shifts in multipolarity). Consider the state’s economic model and domestic political system.

Questions to address:

- How have historical experiences shaped the state’s foreign policy?

- What systemic factors (e.g., globalization, great power competition) influence its actions?

- How does the state’s domestic system align with its foreign policy behaviour?

Outputs: Develop a synthesised explanation of the state’s behaviour across all circles, identifying patterns and deviations from the concentric circles model.

Step 7: Evaluate the model’s applicability

Reflection: Evaluate the concentric circles model’s strengths and limitations in explaining your case study state’s foreign policy.

Questions to address:

- Does the concentric circles framework adequately capture the state’s priorities?

- Are there external factors (e.g., non-state actors, globalization) that challenge the model?

- How might the model be adapted for unique cases?

Outputs: Develop a critique of the model’s explanatory power for the case study and provide recommendations for adapting the framework for broader use.

Step 8: Develop case study conclusions

Provide a holistic understanding of the state’s foreign policy through the concentric circles model: Compare findings across all circles to identify key themes. Highlight tensions between domestic pressures and international actions. Map interdependencies across circles (e.g., how alliances affect core interests).

Outputs: Student groups deliver a class presentation of their case study findings, using diagrams to illustrate the concentric circles and their interactions. Each student should also summarise their insights with an individually researched briefing paper.

References

Shambaugh, D. (2013). China Goes Global: The Partial Power. Oxford University Press.

Kirshner, J. (2014). American Power after the Financial Crisis. Cornell University Press.

Nye, J. S. (2020). Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump. Oxford University Press.

Krotz, U., & Schild, J. (2015). Shaping Europe: France, Germany, and Embedded Bilateralism from the Elysée Treaty to Twenty-First Century Politics. Oxford University Press.

Gambari, I. A. (1989). Theory and Reality in Foreign Policy Making: Nigeria After the Second Republic. Humanities Press International.

Evans, M. (2007). Overcoming the Creswell–Foster divide in Australian strategy. Australian Journal of International Affairs. 61(2) 193–214.

MacDonald, D., & O’Connor, B. (2010). Australia and New Zealand–America’s Antipodean Anglosphere Allies? SSRN Papers.

Wesley, M. (2016). Australia’s grand strategy and the 2016 defence white paper. Security Challenges. 12(1) 19–30.

Buzan, B. & Wæver, O. (2003). Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge University Press.

Hill, C. (2003). The Changing Politics of Foreign Policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Acharya, A. (2018). Constructing Global Order: Agency and Change in World Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Hobson, J. M. (2012). The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760-2010. Cambridge University Press.

Bayne, N., & Woolcock, S. (2017). The New Economic Diplomacy: Decision-Making and Negotiation in International Economic Relations. Routledge.

Bozo, F. (2016). French Foreign Policy since 1945: An Introduction. Berghahn Books.

Oliver, T. (2018). Understanding Brexit: A Concise Introduction. Policy Press.

Cohen, B. J. (2019). Currency Statecraft: Monetary Rivalry and Geopolitical Ambition. University of Chicago Press.

Cooper, A. F. (2016). The BRICS: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Enloe, C. (2014). Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. University of California Press.

Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (2001). Taking Stock: The Constructivist Research Program in International Relations and Comparative Politics. Annual Review of Political Science. 4(1), 391–416.

Grovogui, S. N. (2016). Beyond Eurocentrism and Anarchy: Memories of International Order and Institutions. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hill, C. (2015). Foreign Policy in the Twenty-First Century: Theories, Actors, Cases. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ikenberry, G. J. (2019). After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars. Princeton University Press.

Jervis, R. (2017). How Statesmen Think: The Psychology of International Politics. Princeton University Press.

Jordaan, E. (2003). The concept of a middle power in international relations: distinguishing between emerging and traditional middle powers. Politikon. 30(1), 165–181.

Keohane, R. O. (2005). After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton University Press.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. W.W. Norton.

Nexon, D. H. (2009). The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change. Princeton University Press.

Ruggie, J. G. (2002). Constructing the World Polity: Essays on International Institutionalisation. Taylor & Francis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.